We covered what scene coverage means in film, in the preceding article Build Your Shot List Like A Pro. Covering a scene is often done with many angles of the same action to get enough shots for the editor, but an entire scene on every angle can burn up time and burn out actors.

Contributed by Glen Berry

Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

We cannot shoot everything

The Director must have a refined vision

Provide the editor with coverage

What is Coverage and Shooting Ratio

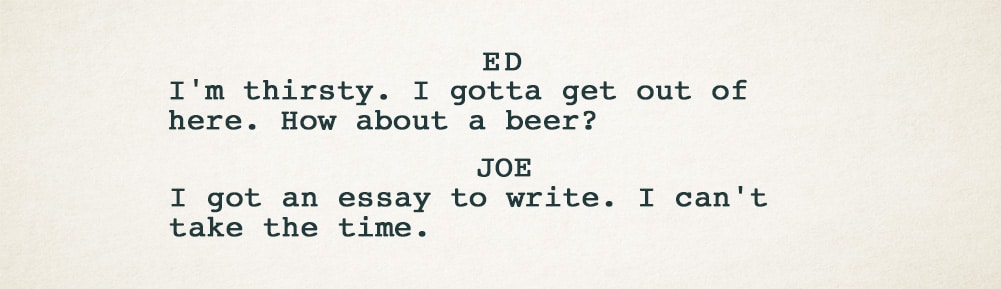

As we see the scene playing out in our heads, we get a read for the emotional material of the scene ahead of time. We start identifying the shots we’ll need to make the scene work. We note the shot types noted on a list – Close Up, Medium Shot, Two-shot, etc.

Coverage is filming enough material from different angles of the same action to provide the editor with sufficient redundant material to flexibly cut the scene together.

We know that enough coverage allows the editor to adjust the rhythm of a scene, even its meaning, purely through the flexibility of shots. If you only shoot one angle, the editor has no choice but to use that angle.

Ideally, we also have to think of how these angles may cut together in the edit. When the scene is edited, its length is a fraction of the total amount of footage we filmed. This brings up the Shooting Ratio.

The shooting ratio is the difference between how much footage we shoot versus how much is used in the final film. For example, if we film 200 minutes of video for a 100-minute edited piece, this is a 2-to-1 ratio (2:1). If we shoot 2000 minutes of raw footage for the 100-minute final edit, we shoot at a 20:1 ratio.

The Cost of Too Much Coverage

While some directors want to shoot the whole scene from every angle to have more choice in editing. Producers are concerned about the shooting ratio.

In the old days, it was because film was expensive to buy and too costly to process at the lab. so we had to plan well for a reasonable shooting ratio – maybe 12:1 for the average budget. This was the limit.

Today, digital media is way cheaper than film, and there are no lab costs. So let’s fire away, right? Not so fast. Math can still kill us.

This is a support article linked from the “Scene Coverage” chapter in Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

While digital media itself is cheaper, time at the backend is not cheap. Think of data management time. Costs of ingesting and drive storage; the labour involved in screening for logging and transcriptions; and the editor’s time for screening and annotating everything. In the end, a high shooting ratio still costs. So ratio costs. Ask a producer.

Sure, when you’re making an eight-minute short with maybe seven or eight scenes, and just a few angles on each scene, fire away. Shoot the full performance with every angle – if your actors can take it. But on longer works like a feature, we have to learn to be more selective. Not only do we plan our shots, but we plan our cuts.

Sure, we still want to give our editor flexibility by providing options, but with some planning, there is a method to being selective enough to respect the shooting ratio while getting enough coverage.

Remember these four rules:

- You Cannot Shoot Everything

- The Director’s Vision is in Charge

- Balance Coverage and Resources

- Plan The Cuts

You Can’t Shoot Everything

For practical reasons, especially for long scenes, we sometimes cannot shoot the entire length of the same action from every angle.

There may not be enough time in the day for it. You wear out your crew and your actors. Performances will not stay fresh after four takes on the eighth angle. There is no need to do all of it. It can be a waste of time.

A seasoned director identifies what parts of each angle of the scene are really necessary, and shoots that – with a bit of overlap at each end of the action.

Be clear on where that shot starts and where it ends, what angle will run into it in the edit, and what shot runs out of it. To do this, you must have a good idea of every shot transition in advance.

Of course, there may be occasional uncertainty on a certain angle from time to time, and the director wishes to cover the entire length for safety from that angle, but this should be more the exception for a confident director and not a habit

The director must have a general plan pre-production and follow through on that plan in production, while still leaving a bit of room for the editor to improvise.

The Director’s Vision is in Charge

The director puts together a plan for every shot and transition and creates that material in production. The editor then reads the material and puts it together the way that the director intended

An editor should be able to look at the footage and read the director’s intent, able to see the plan that the director created just by viewing the footage.

Thelma Schoonmaker has won three Academy Awards for Editing – for “Raging Bull”, “The Aviator”, and “The Departed”. Although enormously talented, she is also very self-effacing. She once said that she did not deserve an award for “Raging Bull”, she simply put it together “the way that Marty shot it”, referring to the director, Martin Scorsese.

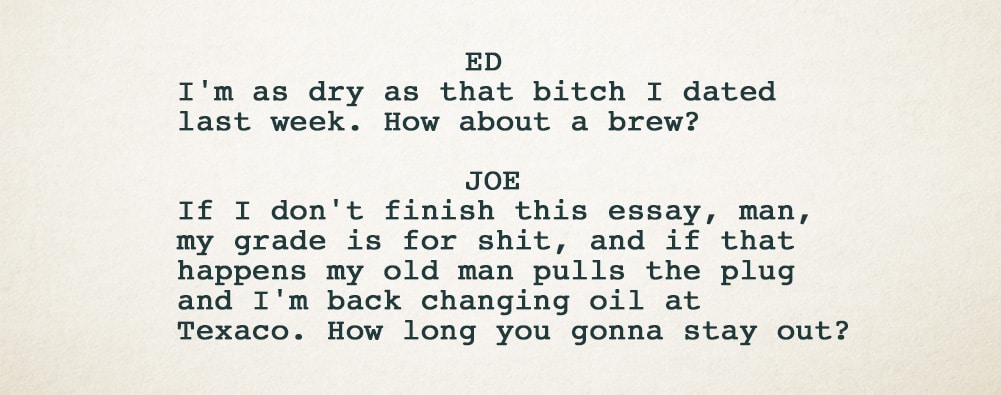

So how do we as directors, plan the cuts in our heads, and shoot for that plan, while still giving our editors some flexibility to transition between shots? The first step is to find the moments in the scene where you will need each shot and when we will not need each shot.

Balance Coverage and Resources

We need to make decisions as directors. We have a read on the emotional material of the scene, we should be able to select moments in the scene where we will need certain shots and other moments where we will not.

As you will recall from the “Fistful of Dollars” example, the scene’s classic construction moves between wide shots and closer as it builds to the climax.

Suppose, for example, a director’s vision may not call for a wide shot at the climax of the scene. Instead, the director wants to be tight on the actors at the climax to see the expressions on their faces. The wide shot may be useless for that, so in the director’s opinion, there is no point in shooting that portion of the action wide.

In doing this we create intentional ‘gaps’ in our coverage, where parts of the action have not been covered from certain angles. But these gaps should be planned out in advance, while still allowing enough overlap for key bits of the action.

Conclusion

We want sufficient coverage to cut the scene together, cover the action, and provide options to the editor without shooting the entire scene from all angles. We seek a balance between flexibility and the resources (energy and time) we expend on coverage.

Many moments can be exploited by the editor to make a seamless transition but the savvy director would be wise to know where they are in advance and incorporate that into his or her plan for when to start and end a shot.

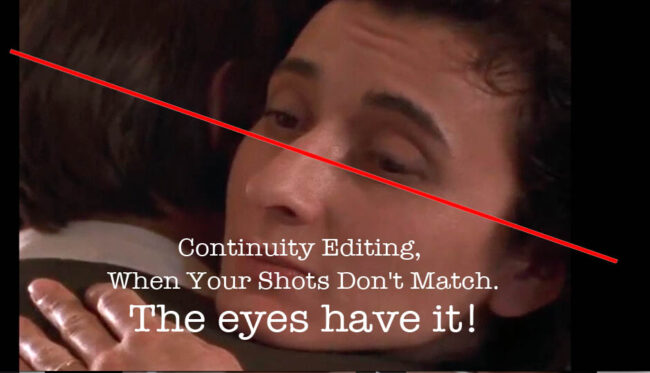

Knowing where these transitions (or cuts) take place requires at least a little knowledge of editing and some practice.

In the meantime, on your short films with fewer angles and brief scenes, go ahead and shoot everything on every angle; over time, with enough practice in shooting and cutting these films, you exercise the ability to plan your cuts, better preparing you to engage in longer and more complex projects.

SUMMARY

The director cannot shoot all angles in their entirety. It can wear out the cast and crew, waste time and kill morale. The director must have a vision.

The director must know all angles and perspectives and make decisions about what parts of the scene to cover from which angles.

Give the editor options by covering the action in the scene from more than one angle.

NEXT >>>

PLAN YOUR SHOT TRANSITIONS

to allow for smooth edits

<<< PREVIOUS

BUILD YOUR SHOT LIST

An Analysis of Scene Coverage

from Sergio Leone’s “A Fistful of Dollars”

Fast-Track Into 1st-Year Level Film Education

Made for Apple Books

Get beyond mere tips & tricks and how-to tutorials. This beautifully designed learning system is both a textbook and a structured course in one volume.

Learn from it. Teach with it. Gift it.