Less is more: Learn some minimalist screenplay techniques that successful screenwriters apply to streamline dialogue and action in their script to make for an easier read.

Written by Charles Deemer

Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

‘Less is More‘ is a surefire and lasting dichotomy in the screenwriting business.

Let’s look at how to put this philosophy into practice when revising the draft of a screenplay.

I’ll focus on two areas where my screenwriting students do most of their overwriting: The dialogue and the description (action).

Less Dialogue, Please

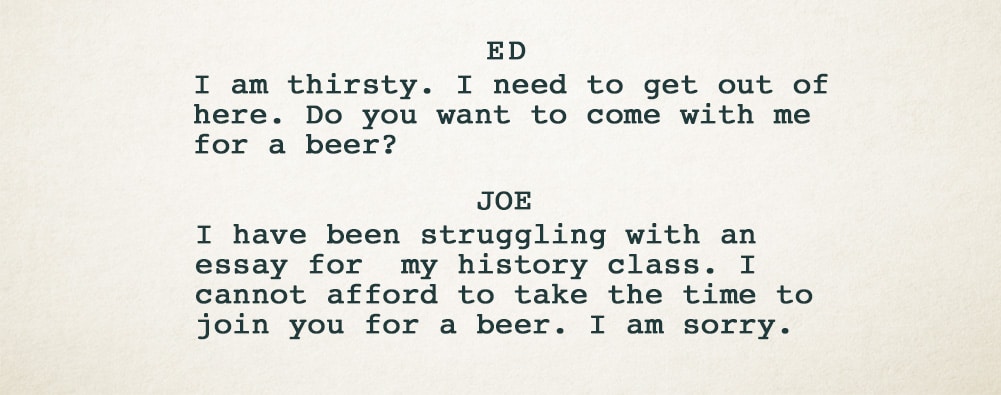

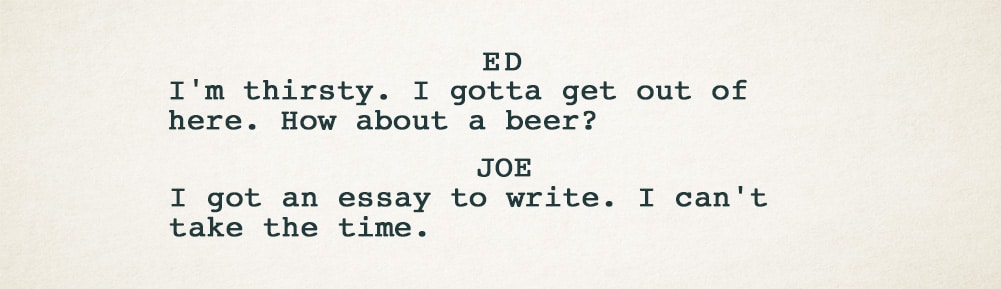

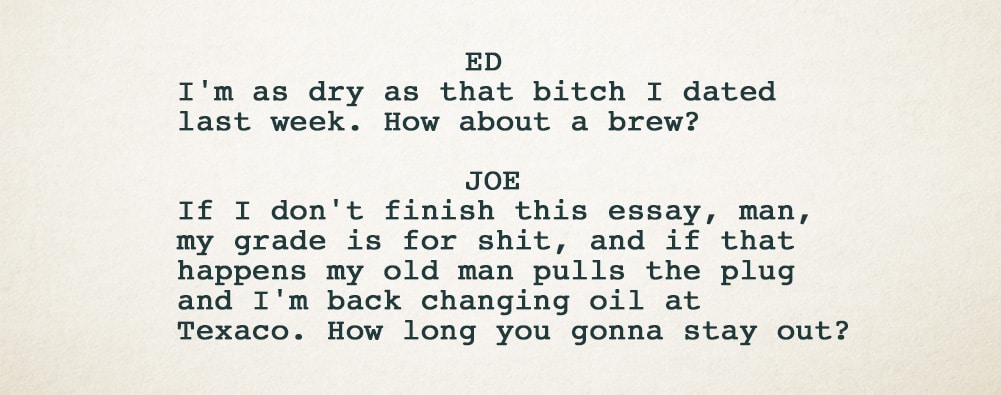

Often one glance will tell if a scene has a dialogue problem. This is when a series of long speeches are exchanged, each consistently taking up more than several lines in the block of dialogue text.

One character speaks for a dozen lines, the other answers for a dozen or so more, and so on. Large blocks of dialogue text fill the page.

However, there are exceptions. For example, the first 45 minutes of “Tar”(2022) is almost exclusively dialogue. If not for someone as capable and thus watchable as actor Cate Blanchett, perhaps the criticism over this wouldn’t be as evenly split. Still, a daring move.

I commonly see this problem in a student script. If the exchange is much too verbose, repetitive, and therefore boring, I copy the pages to do a classroom exercise.

I pass out the scene as originally written, select students to read the parts, and direct a staged reading. We discuss it.

The scene readings of large exchanges of dialogue are usually painfully slow. The class quickly picks up on this. They identify the common moments of repetition that happen in such scenes.

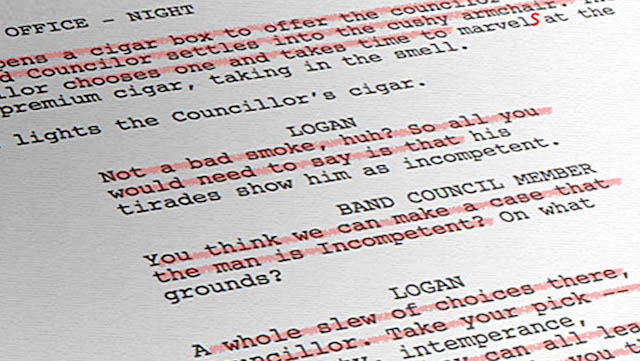

Then I take out my red pen and very dramatically start crossing out lines.

Over the years I’ve learned that most fat in a long speech comes in the middle. So in a 12-line speech, I might cross out lines 3 through 11, leaving the first line second, and the last – and that’s all. Maybe I add a phrase to make for a smooth transition.

I continue this through the entire scene, crossing out half to two-thirds of the dialogue. Then we replay the scene out loud.

The improvement is astounding! The pace immediately quickens. The exchanges are quick and snappy, not long and verbose. There is no repetition to cause boredom.

The class may think I’m a magician, able to fix a scene so dramatically by doing nothing more than hacking out excess lines of dialogue.

I’m not a magician. I just have experience. I’ve read thousands of pages of verbose, over-written dialogue. I can spot it half a room away.

The key test to any line of dialogue in a script is this:

What is lost if it is removed? If precious little is lost, then cut it.

Every line of dialogue needs to move the story forward in a fresh way or make a point about a character that we don’t already know.

Verbosity is your enemy. Less is more.

This is a support article for Cyber Film School’s

Multi-Touch Learning System 2022 Edition

Less Description Please

Here is the description of John Nash’s fantasy CIA connection in, ‘A Beautiful Mind’:

“Fine dark suit. Thin tie. WILLIAM PARCHER.”

This is as much the character description as we get on this guy!

Here is how we meet the title character in ‘Citizen Ruth’:

“She is around 30.”

That’s all we’re given.

Clarice Starling in ‘Silence of the Lambs’:

“Trim, very pretty, mid-20s.”

That’s it.

The antagonist, however, gets more detail because he or she is more unusual:

“A face so long out of the sun, it seems almost leached

– except for the glittering eyes, and the wet red mouth.”

Descriptions of place get no more detail than descriptions of character. From Sling Blade:

“It’s an all-American girls’ room. Everything is pink.

There are stuffed animals everywhere and posters of pop idols.”

From The Ice Storm:

“A large New England Colonial,

with a few modern additions and touches.”

From Good Will Hunting:

“The bar is dirty, more than a little run down.”

None of these comes close to the long, verbose descriptions of character and place that my students love to write about, especially those who come from a background in literary fiction.

None of this detail is appropriate in a screenplay. Why? For one hugely important reason:

The screenwriter is a collaborator.

The Screenwriter is not the costume designer, not the set designer. A screenwriter sticks to a “fine dark suit” and lets the costume designer pick the color.

She writes, “a thin tie” and lets the wardrobe people decide just how thin.

A screenwriter offers, “stuffed animals everywhere and posters of pop idols,” letting the set designers select which animals and which pop idols belong on the set.

Write so it doesn’t sound like you are telling the costume designer and the set designer how to do their jobs.

Your job is to give them the appropriate clues so they can do their job in a way consistent with the context of the story.

Write with an awareness that you are a collaborator. Understand this and you will solve your tendency to over-write descriptions.

Make sure to read our related articles for a deeper look into streamlining your draft:

Writing Is Rewriting

Vertical Screenwriting For An Easier Read

The Writing and the Story

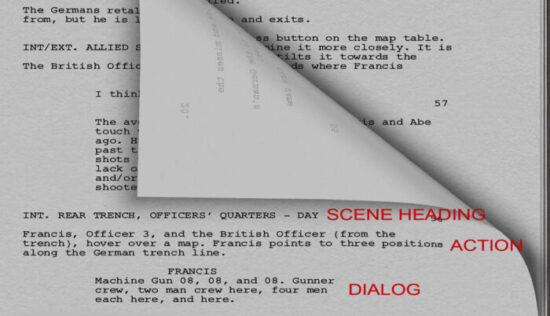

As we tend to repeat in many screenwriting articles, the screenplay is a blueprint for a movie.

It should be written accordingly, lean and mean, in a style that lets the story flow quickly, vertically, down the page. Your job is not to let the writing get in the way of the story.

Think about that.

What an odd thing to tell a writer! Don’t let the writing get in the way of the story.

Many of us are taught early to think about “writing” the way a novelist thinks about it, where every essence of the story, and literary style, is everything.

The screenwriting style is far more subtle and more poetic because there are far fewer literary tools to use.

When beginning screenwriters over-write, they often let the writing get in the way of the story.

Excess verbiage becomes camouflage that hides the story’s movement, leading to misdirection from the spine of the story that needs to be abundantly clear quickly and throughout the script.

Don’t let this happen in your script. Make your writing serve your story because a producer isn’t going to buy your writing, he or she’s going to buy your story that reads like a film.

“When in doubt, leave it out!”

Browse more articles:

LEARN SCREENWRITING

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.

Charles Deemer authored Write Your First Screenplay among other titles and taught screenwriting at Portland State University.