Contributed By Charles Deemer, edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

If you are a student of screenwriting and not confused by screenplay format, then you haven’t been paying attention. Conflicting information is everywhere. This is unfortunate because, in fact, the preferred format for the contemporary spec screenplay is straightforward and easy to understand. But today’s format took years to get there.

The Origins of Confusion

Then why the confusion? For three major reasons: first, screenplay format has evolved in major ways over the years; second, established writers tend to use whatever older format with which they learned the craft; and finally, published screenplays are shooting scripts, not spec scripts, which contain significant format differences.

Someone should write a book on the evolution of screenplay format. It’s a fascinating subject. I remember looking into screenwriting in the 1960s and quickly abandoned it because the screenplay format was filled with technical jargon that I was too lazy to learn.

Terms like “TWO SHOT” and “DOLLY SHOT” and other camera direction in screenplay writing was everywhere. In those days, the screenwriter contributed to directing the film by including in the script precise directions for how the camera would shoot the scene.

However, directors went ahead and did what they wanted to do, regardless of “in script” direction, so format change was inevitable in order to make the screenplay a more clean and efficient “blueprint for a movie.”

Directors, not writers, were going to direct the film and the format was destined to change to reflect this reality. The scripted scenes were subsequently written and read in a master scene format with very few if any, camera or editing cues.

However, there are interesting hacks that experienced screenwriters use to “direct without directing” by using white space to break down the action into several beats, as if each action is one visual setup. More about this in our article Writing Screen Action – Part Two.

Taking Power from the Writer

Therefore, the evolution of format has been in the direction of removing directorial power from the screenwriter. This process was gradual. After specific camera directions dropped out of the accepted format, general directions replaced them.

Instead of technical terms like “DOLLY SHOT,” writers would describe the same thing in more general language: “the CAMERA MOVES along with them as they walk down the street.”

Later, in the eighties, new fashionable terms came into place that suggested how a scene would be shot. ANGLE ON became a popular slugline and sometimes the name of the character would become a slugline, suggesting the same thing.

This post is a support article for the “Screenwriting” chapter in Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

Today’s ‘Master Scene’ Script

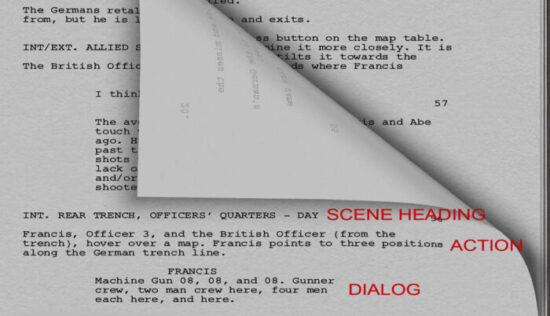

This process continued to evolve until all references to the camera were removed from the spec script. Today’s spec script is written in “master scenes” using four elements.

1. THE SLUGLINE:

Almost all sluglines begin with INT. or EXT. for interior or exterior respectively. There are very few exceptions. One is SUPER, a slugline put before language superimposed on the screen, such as a place or date: SUPER: “Three years later”

Another is INTERCUT, used for a phone conversation after the location of each party is established with prior sluglines.

If you write all your scenes with sluglines beginning with INT. or EXT., you are on the right track. Location and time follow:

INT. JOE’S HOUSE – BEDROOM – NIGHT

Always use FULL sluglines and always use day or night unless a special time of day is dramatically essential, i.e. two lovers watching the sun rise: EXT. BEACH – SUNRISE.

2. THE ACTION ELEMENT:

Write, cleanly and crisply, what the audience sees on the screen. Do not write action in parentheses after a character name, i.e. GEORGE (lighting a cigarette), which has fallen out of fashion. Cap a character name in the introduction only.

Here, in the action element, is where most beginning writers over-write; I’ll have much more to say about writing action in a future column.

One more thing: write in small paragraphs, no more than four or five lines per paragraph, then double-spacing to the next paragraph. In fact, by isolating action and images in their own paragraphs, the writer suggests visual emphases in the story, the only remaining way a writer can contribute to direction.

3. CHARACTER NAME:

Always in caps, tabbed toward the center of the page. Be consistent. Don’t call a character JOE here and MR. JONES there.

4. DIALOGUE:

Tabbed between the left margin (where sluglines and action are) and the character name margin. Writing dialogue is an art in itself, and a future column will be focused on it.

Beginning writers also over-write dialogue, making scenes slow, chatty, and “play-like.” Remember, people don’t talk as formally as they write. Your dialogue should reflect the personality of each character.

SUMMARY

Here is the style as seen in the best contemporary spec screenplays today:

- Crisp visual writing (what do we see on the screen, in general terms?) in simple sentences,

- in short paragraphs, with no mention of the camera,

- and without directing the actors or usurping the duties of the costume designer, set designer, cinematographer, etc.,

- with dialogue scenes that are short and snappy.

Remember, a screenplay is not a literary document. It is a blueprint for a movie.

Make it lean and easy to read — in fact, easy to skim because all screenplays are skimmed or read over very quickly before they can reach the next plateau to be read more carefully.

In “VERTICAL WRITING FOR AN EASIER READ”, we explore formatting that allows for a more efficient read.

If a brilliant script isn’t an easy read, it will never make the first cut. The purpose of format today is to make reading easier than it ever was. If you write in master scenes, you will accomplish this.

Get the full picture with Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook