Evaluating your own screenplay depends on the quality of questions you ask yourself, making the difference between pulling the plug or moving forward.

Contributed By Glen Berry, Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

Important Concepts

• Wait until the script is ready

• Know yourself

• Writing is re-writing

As we toil through the lonely landscape of the screenwriter, we often discover that translating certain concepts into viable, exciting stories is not easy. Certain ideas we come up with simply do not translate well into film – not immediately. They require more thought and more background work.

Some aspects of the idea are compelling, but other parts wanting. The solution is to invest time, exercise patience, and persist. Keep working toward solutions that make your idea work. Sometimes it just takes time to find creative inspiration, to find the right key that unlocks the creative puzzle that’s been trading your mind.

Be Patient

Do not let those around you pressure you into moving to pre-production with an idea that you feel is half-baked. Instead, pitch it to people you trust, talk through it, and ask for feedback.

You will know when you are ready to move forward. Sometimes, though, we don’t have the luxury of waiting – projects most often have deadlines. That means working with limitations and constraints.

As you get more practiced, the quality of the questions you ask yourself can make the difference between pulling the plug or moving forward.

What To Look For

Begin looking for the central idea. Does your script fully express a central idea, or is it reading like a short lead-in to a yet unwritten longer piece?

This is an easy pitfall to fall into if you are writing a short script. If your short cannot clearly articulate that idea, at least to yourself, you do not have a script worth producing.

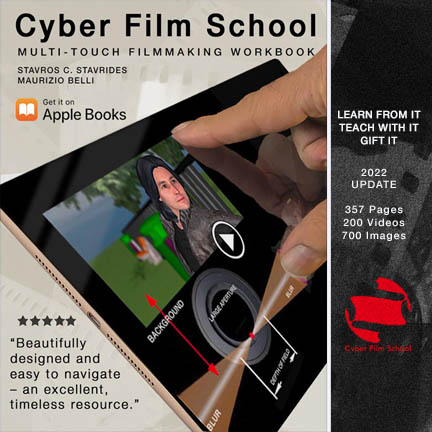

This post is a support article for the chapter “Screenwriting” in

Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

Evaluation Structure

Applying an evaluation structure will help you find what it is you are trying to say. It is a method of introspection that helps the writer look inside themselves and see what it is they want to express. An evaluation includes a study of:

- Conflict and Resolution

- Main Character’s Motivation

- Depth of character

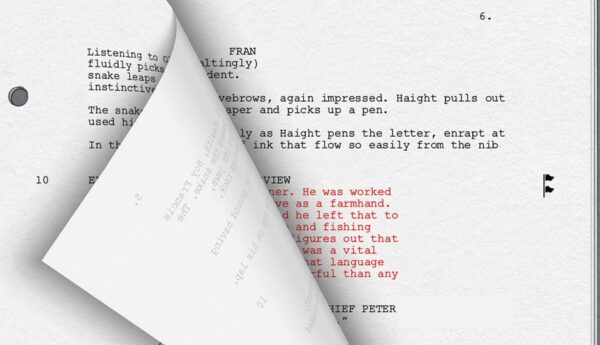

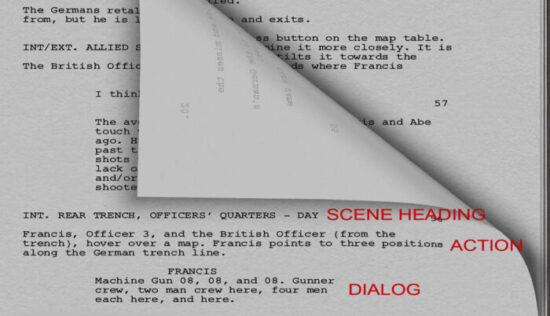

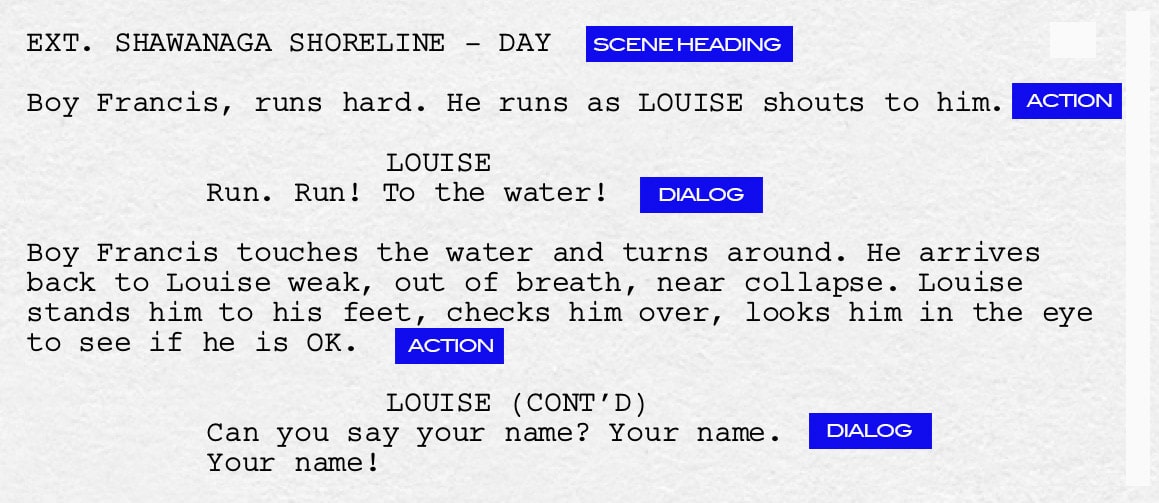

- Formatting: balance between Action and dialogue

- Visually clear action that aids the reader in visualizing the film the action

When you read your or someone else’s script, look to see what the story’s conflict and resolution say about their idea.

You can also read your main character’s motivations and arc through the story and make an evaluation of the script. Is the character real, believable, and three-dimensional? If the character is unbelievable and one-dimensional, does it fit well with their concept? If you can’t get a handle on the character and why they do the things that they do in the story, chances are the writer doesn’t understand the character either.

Remember to watch formatting and the balance of dialogue vs. action. Is it told cinematically through action or does it depend on heavy dialogue like a stage play? Has the writer considered that this script will actually need to be shot? Is it written in such a way as to communicate clearly the vision of the film so every member of the crew can envision it, especially the producer, director, and actors?

Answering these questions helps shape your script. Showing your script to others, like pitching an initial concept, is part of the feedback loop that can help guide you in finding answers to problems with your project.

How to Handle Feedback

Knowing what feedback to incorporate and what feedback to ignore is a valuable skill for the writer to develop.

Too many times, writers ignore helpful feedback – they don’t want to hear the problems with their work. But those problems get amplified down the production line and a smart producer will task a pass on a flawed script.

Other writers tend to incorporate all the feedback they get and lose some of their own spark and conviction that gave life to the project at its inception.

Incorporating all feedback will lead to a weak and watered-down script. In the film business, every person has their own take on the material, so a good writer must be able to find some balance and work with notes that enhance the work.

Know yourself. Do not take feedback personally, but do listen and consider their words carefully. If you are eager to get direction from others, you need to incorporate their suggestions, if sometimes reluctantly.

Writing Is Rewriting

Remember: writing is rewriting. Get the first draft down on the page so you have something to work with, but consider it a paper-maché sculpture.

It’s only a sketch that you will adapt and change and mold into its final form. No one puts words on paper perfectly the first time, especially not a script. Write a draft, get feedback, and rewrite. Work on it until it is flawless.

You’ll never please everybody but if you are demanding of yourself and your idea, you will know when it is done.

If you get so stuck with an idea that you don’t know how it will work and none of the feedback you get is leading you in the direction that is going to improve it, scrapping the idea and starting over is always an option.

If the concept is important to you, you will come back to it. The answer to making it work may come to you in a dream three years from now.

If you cannot make it work now, you can make it work later. Ramming your head against a wall isn’t going to solve anything. Set it aside and come back to it.

In the meantime, strike out a new idea that flows better onto the page. Your second script will be better than your first script, your third better than your second, and so on. The important thing is to write and get them done.

Summary

• Do not allow your script to go to production until all of the problems have been addressed.

• You have to know yourself, know what feedback to incorporate, and what feedback to reject.

• No one puts words onto paper flawlessly the first time. Be hard on your idea and work through every aspect until it is perfect.