When I’m talking about scene design, I’m not referring to the furniture in a room or what’s hanging on the wall. I’m talking about how a writer, and later a film editor, structures each scene in a screenplay.

In particular, I’m talking about the length of those scenes, which is determined by when a scene begins and when a scene ends.

By Charles Deemer, Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

UPDATED DECEMBER 7 2022

This article gets to the screenwriting application of “Exit Late, Start Early”. We further cover this concept for film editors in our article Three Pitfalls of the Editor. You’ll find this link at the end below.

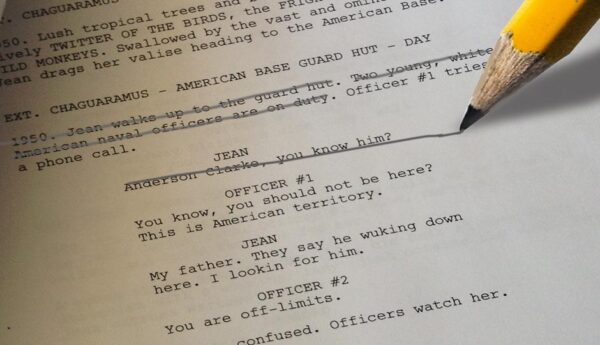

Typically, a beginning screenwriter will write scenes that are too long, and that are too inefficient. This error is pandemic because screenwriting is the most efficient narrative form we have.

Every word, every moment, has to matter in a screenplay. Beginners almost always begin their scenes earlier than they should and then carry them on longer than they should. So…

When Should a Scene Begin?

A screenplay is built in modules, scene by scene. For this reason, it is difficult to talk about any single scene out of the context of the whole. All the same, basic principles of efficient scene design are part of the screenwriting craft.

A scene in a screenplay should begin as late as possible. What does this mean? Let’s take an example.

A husband and wife have been separated. The husband is the protagonist in the story. He and his wife are meeting for lunch to talk about their future. The wife is going to tell him she wants a divorce.

Most beginners would spend a lot of time getting the husband to this lunch meeting. He might take some time to decide what he is going to wear. He might dawdle on the way, so as not to be early and appear to be anxious. He might fortify himself with a drink or two. Finally, he’ll be met at the restaurant by a hostess and led to the booth where his wife waits.

There will be small talk. A waiter will take an order for drinks. More small talk. A waiter will take their lunch orders. More small talk. Eventually, they’ll get around to talking about their marriage, at which time the wife will say she wants a divorce.

Although there are dramatic contexts in which this slow development can work (see below), in most cases this scene will be too slow. It has too much fat. What is the point of the scene? The news of divorce. A more skilled screenwriter, therefore, would open the scene just before this moment. The couple is already seated at lunch. They are eating silently. Suddenly the wife pops the news.

But there is a context in which the slow version is stronger than the more efficient version. Let’s say that while getting ready, the husband fetches a handgun, loads it, and hides it on his person.

Now where there was slow development and fat before, there is tension because we are on the edge of our seats, wondering what he is going to do with the gun. And the longer we have to wait, the tenser the story becomes.

In other words, for slowly developing scenes to work, there must be an element to justify their pacing; in general, the crisper the scene, the better.

So what about getting out of this scene?

When Should a Scene End?

In the first version, without the gun, beginners would have the wife pop the news and have this lead into an argument, probably the kind of argument we’ve heard many times before. This argument may take several pages, even though we learn nothing new from it.

A more skilled screenwriter might have the wife’s news be the last line in the scene. A quick look at the husband’s reaction and cut: maybe to the husband having a drink in a bar, talking with a friend, or sleeping with his mistress.

Once again, the gun changes everything because it adds a dynamic new element to the dramatic mix. The wife gives the news. A beginning writer might have the husband take out the gun and shoot her. Chaos results. The husband is wrestled to the ground by customers. He barely gets away.

A more skilled screenwriter would surprise us. The husband takes out the gun and points it at his temple. Would he really? The wife looks like she’s about to have a heart attack. He pulls the trigger. Nothing. “I was going to shoot you but I chickened out,” he says. “I took out the bullets. Have a nice life.” He leaves.

This post is a support article for the “Screenwriting” chapter in Cyber Film School’s

Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

Effective Scene Design: ‘The Birdcage‘

Hollywood has mastered good scene design and even otherwise poorly crafted movies are likely to have efficient scenes. But good movies, of course, use good scene design to better dramatic effect. In my University screenwriting class, I use The Birdcage as an especially good example of film storytelling with efficient scene design.

Let’s look at two scene transitions from The Birdcage.

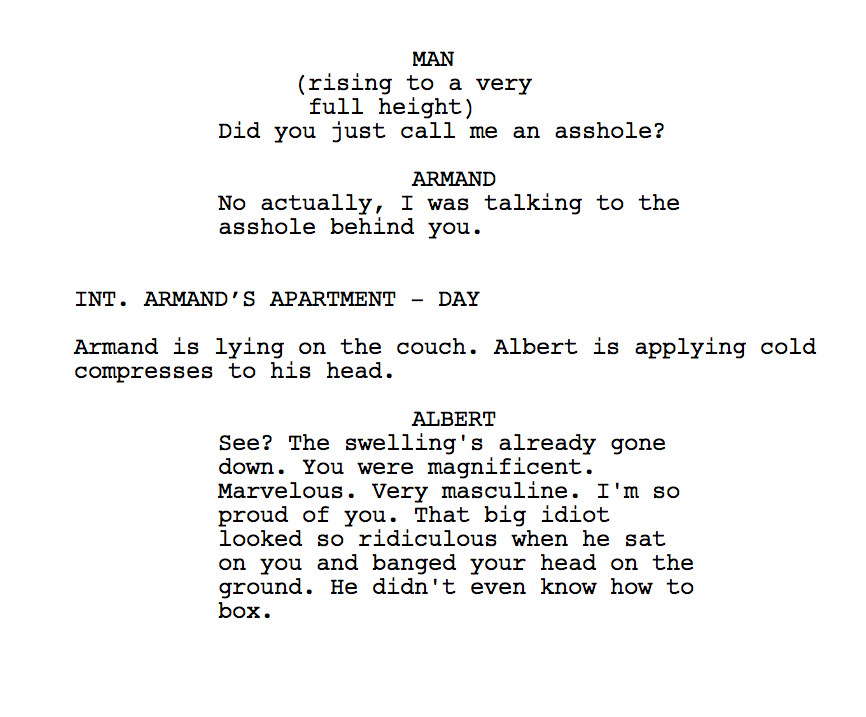

In the first, Armand has been trying to teach Albert how to walk like a man. When Albert accidentally bumps into a customer on the patio, Armand rushes to his defense like a macho hero. The customer stands up. Here is what follows:

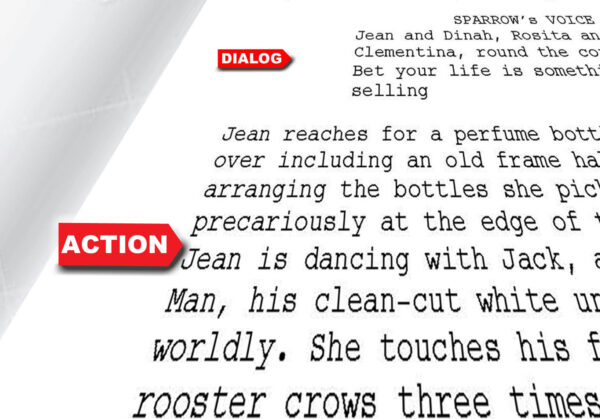

Study this transition carefully because it reveals the key to efficient scene design. What is left out is as important, maybe more important, than what is left in. Notice that what is missing is the physical confrontation itself. In a comedy like this, physical violence would be inappropriate and Albert’s subsequent description of the fight is far funnier than seeing the fight.

A beginning screenwriter would take a page or more to make this transition. We’d see the fight, and we’d see Albert helping Armand get home, and we’d see Albert helping Armand to the couch and running off to prepare cold compresses. But in the context of the story, all those details are irrelevant.

The story itself always determines what details you need to show because they support the story and move it forward, and which details are “fat” because they do not move the story forward.

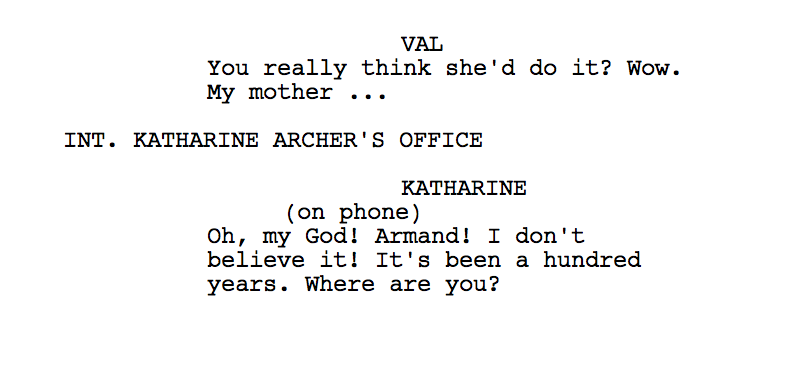

Another example. Armand has come up with the idea that Val’s mother might help them in their charade as a straight family. Here is what follows:

Again, this transition has great efficiency, leaving out all the unnecessary details that a beginner would put in: Armand’s going to the phone to make the call, a secretary at Katharine’s office answering the phone, and so on.

Tips

Although it is always the particular context that determines scene design, there are some principles that will help you make tighter scenes.

Think of ending a scene with a kind of “punch line” or a moment that raises or asks a question. Each naturally leads to something new, the next scene.

Think of scene beginnings as starting in the middle of an action at the point where new story information begins to be revealed.

In other words, cut all the “set up” material of the scene and let the context itself set the scene. Get to the point of the scene from the beginning

Admittedly, there are other factors that justify more leisurely scene development, such as pacing and suspense. If we see a serial killer hide in the closet as a woman comes into her apartment, that knowledge will keep us on edge for a much longer scene than we’d accept otherwise, if the apartment were empty. We are constantly thinking, “Is he coming out?”

But in general, the problem beginners have is putting too much detail into a scene, starting it too early, and ending it too late.

If you concentrate on scene openings and endings when you rewrite, cutting from the top and from the bottom, you should learn to write tight, focused scenes that have no fat and no dull moments.

Be sure to read further applications of “Exit Late, Start Early” in film editing in:

Three Pitfalls of the Editor.

<<BACK TO: Learn Screenwriting