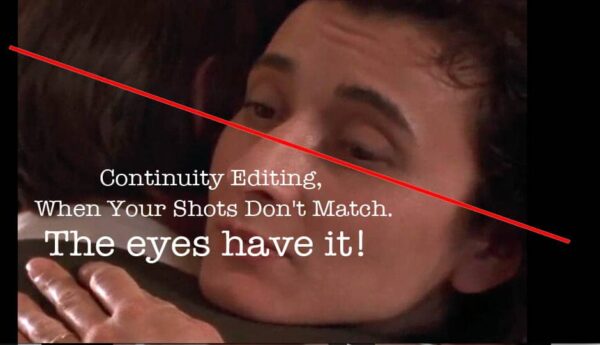

What could be a frightful continuity error for a newbie editor, is a fresh challenge for a pro editor to solve – “Focus on the eyes!”

Continuity & Rhythm in Editing

But sometimes the editor is handed a set of shots – long, medium, close, cutaways, cut-ins, etc. They are meant to be cut together ‘seamlessly’; the action is supposed to match where one shot cuts to another as a continuity cut.

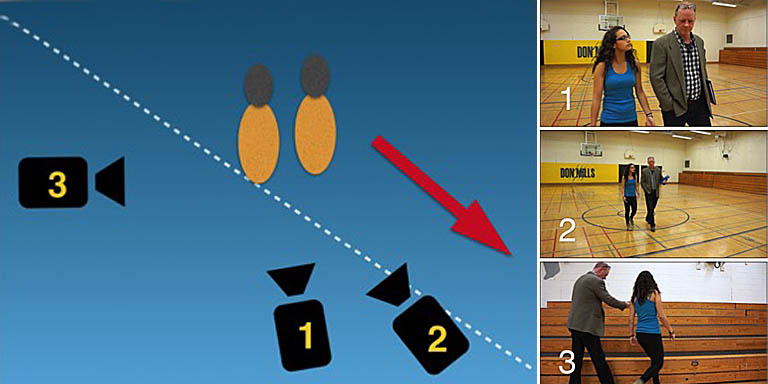

Below is a continuity editing example in a dance number between Sean Astin and Emily Hampshire. The scene is covered with several shot sizes of identical action. When edited, the action appears continuous as the shots intercut.

The most common mistakes have to do with continuity and rhythm, which both rely on the quality of the number of shots that cover a scene.

This article is a reformatted excerpt from “Scene Coverage” in Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

Solving Continuity Issues

During production, a few continuity details get missed while covering a scene – a cup in an actor’s left hand in one shot changes to her right hand in the next. The clothing does not match as we cut from one shot to the next.

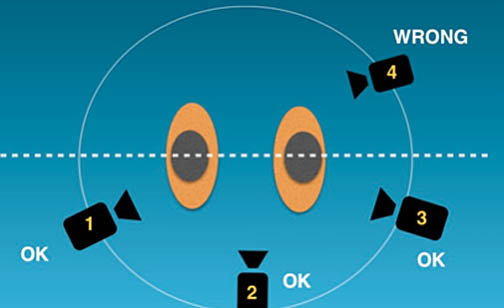

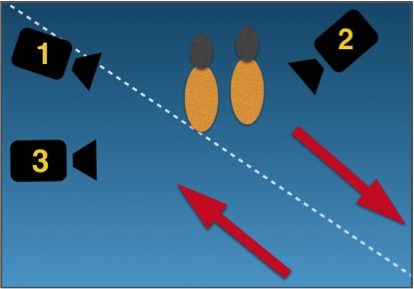

Screen direction problems show up where an actor or camera has crossed the axis, so when the shots cut together actors suddenly face the wrong direction. See our article on maintaining Screen Direction issues here.

New editors often fret over these flubs, but what is a continuity error to a newbie is a challenge that seasoned pros look forward to solving. Their solution is to focus on performance and eye lines and performance

In the following example, we forced the cut without strict continuity on the action. However, the eye line is consistent and we follow the flow of the story through the actors’ connection.

Now replay the above and examine the woman’s hands. Notice that in each cut, they do not match the action.

Even when they embrace, we jump forward in time. We don’t notice the mismatched action because the editor draws us to the performance. We are caught up in the scene’s rhythm.

“Dede” Allen was one of cinema’s all-time celebrated ‘auteur’ film editors, and the very first editor to be awarded a single-card head credit as Editor, which is now commonplace. She’s known for The Hustler (1961), Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and Reds (1982). She was also known as Hollywood’s ‘go-to’ film doctor to fix problems in major studio films.

To solve continuity issues between shots, Dede advises to ‘cut’ with the performance, with the eyes.

Importance of Rhythm

Continuity in a film is not the only consideration when editing a scene. Although rhythm in editing is less about movie continuity, it is more related to continuity in terms of conveying ‘subtext’. Let’s explore subtext.

Picture this: an editor cuts a scene following the script exactly as written. His cuts are smooth and perfect. The director screens it, then yells to the editor, “You missed the whole point!” Much like cracking a good joke, telling a story is all in the timing or rhythm, which may not be evident on the script page.

The editor in this scenario mistook pauses in the performance as “dead space.” Editors must screen everything and know the story and director’s intent in order to spot the subtext and cut accordingly. The subtext is what the character thinks or believes. It’s often found in silent pauses, over which the editor has full control.

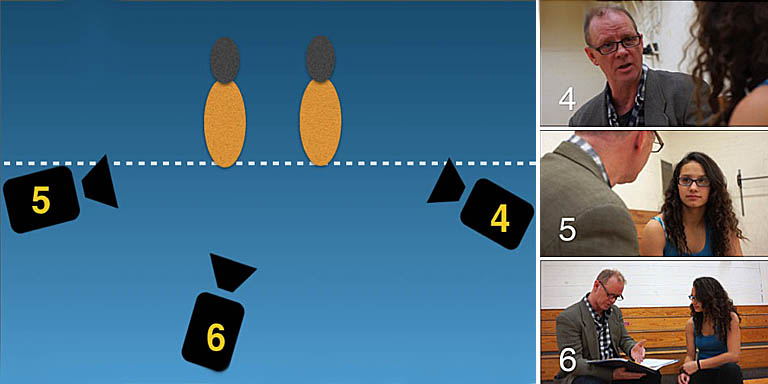

In the back-to-back clips below, spot the truth and the lie in this dialogue: One dialogue scene is cut two different ways – same setup, same script, same dialogue. The first cut sounds like a straight-up explanation. The second cut lets us read the behavior of the players and what they are saying to each other.

<< BACK TO: Three Pitfalls of the Editor