When it comes to the rich quality of a well-made film that successfully connects with its audience, crappy sound will kill any visual magic you worked so hard to show off.

By Glen Berry

Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

Bad Sound Equals Bad Movie

Bad sound can undermine every noble effort you’ve made for an otherwise flawless film; your pro camera work takes a nose dive, your crafty editing goes unnoticed, and you wasted your time on that perfect color cast.

Why? Because your audience was distracted. By bad sound.

If you going to forego some effort in the sound department because you can’t afford it, or worse, know little about it, stick with making a finely crafted silent flick that ropes in a crowd.

This cannot be overemphasized. (Really, this cannot be overemphasized).

A filmmaker, whether newbie or crusty old sod, has so many things that deserve their time and attention when making a movie: script, performance, production design, scheduling, budget, image, lighting, crew biting at your heels, the bank rep calling again, the list goes on.

All of these things really need attention and energy, pronto. But amid all that stress, one thing that the filmmaker cannot afford to forget, and the one thing that costs relatively little to get right, and is absolutely essential to the overall vision, is (you heard it) sound.

An audience will walk out of a movie that may have a great image and bad sound. They’ll less likely to walk out of a movie with a rich, layered soundtrack that accompanies a somewhat hurting image.

We cannot treat sound as an afterthought, an item you get to when everything else is done. It’s not something you just hand off to a technician to grind out in the remaining moments before the deadline, with the last 79 cents in your budget.

And be warned: referring to the postproduction sound artists and craftspeople as ‘technicians’, may get you seriously hurt.

David Lynch said, “Films are 50 percent visual and 50 percent sound. Sometimes sound even overplays the visual.”

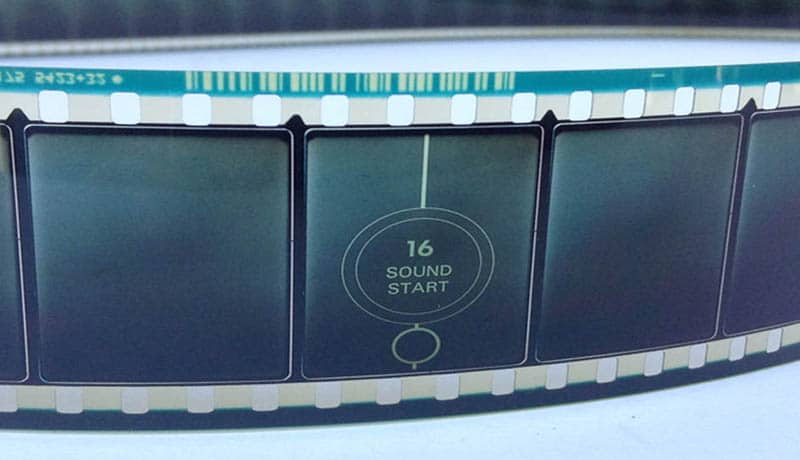

The Sound Track

It’s a popular misconception for the general public to understand “Sound Track” as the music compilation of pre-recorded songs made for a particular movie. That is a misappropriation by the music industry’s marketing folks. Rightfully, however, the term did begin with “From the soundtrack of…”, then eventually got shortened to the misnomer.

The “soundtrack” is simply the synchronized audio that runs alongside the picture element of the movie. It is comprised of four main elements:

- Dialogue (Production Track & ‘ADR’)

- Narration

- Sound Effects

- Music

Dialogue

The Production Track

‘Production Track’ refers to all audio that has been recorded during production, that is delivered to the post-production phase.

Dialogue forms the key element of the Production Track, so we call it Production Dialogue.

Dialogue recorded during production needs to be clean, clear and flawless. This will depend on the location, where we need to deal with background noises, proper microphone selection and placement, even as subjects are on the move.

The well-trained recordist must understand the recording signal strength of audio being laid onto the recording medium while monitoring quality with a pair of highly trained ears.

There’s only one chance to get it right, and that is when the actors deliver their lines on the set. If the dialogue track is muddled, weak or riddled with pops and hisses then it will make it next to impossible to deliver a quality soundtrack.

A certain amount of dialogue track can of course be ‘cleaned’ in post-production needed to remove pops, hums, hisses and other undesirable sounds, but it will sound ‘almost’ good.

The lower quality of the production track that makes it to post-production, the more time you will need to spend in post-production. In most cases, this process of cleaning will work to cover minor and occasional problems. Don’t depend on it.

There will always be issues that need to be fixed, but you want to spend your time in production creating great sound, and not fixing problems in post.

Re-recording dialogue in post-production can be expensive, and never easily matches the authenticity and emotional tone of the moment the actors interacted on set.

However, there are times when it is unavoidable. which brings us to ADR.

This article is drawn from the “Sound” chapter in Cyber Film School’s

Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

‘ADR’ Track

Automatic Dialogue Replacement (ADR), involves bringing an actor into a sound-proof space and re-recording dialogue that was either not recorded in production or was found to be unusable. It is common to need to pick up a line or two of dialogue in post-production.

Shooting next to a stream, in a factory, or on the tarmac at an airport may make it impossible to record decent sound in production. However, the more ADR that is done in post, the more likely it is that lip sync will not be perfect. But in experienced hands, it’s barely noticeable.

Narration

Although narration is not a component of every soundtrack, it should be considered a separate element. In factual work its role is obvious. In fiction work, it could be the voice-over of the protagonist offering a first-person context to the predicament.

The editor’s task when cutting narration into a factual sequence needs to assure good rhythm between picture and narration.

A first-pass narration reading (the ‘scratch track’) of the script by either the performer or a temporary reader can allow the editor to play between the picture and sound when creating the first cut. The scratch track helps get the length of the picture, and the script may be adjusted to suit.

The final narration could be recorded at any point in the post-production process. Although normally recorded in a studio space, narration can be captured in any reasonably sound-proof space.

Sound Effects

Sound effects add richness and depth to the soundtrack and can often include a vast number of tracks.

Although they sometimes come to the foreground, sound effects are often most effective as subtle textures that have a subconscious effect on the viewer.

Sound effects can sync to action on the screen, come as a mixture of background sounds known as ambience or be completely artificial, not found in nature sounds.

A sound designer is tasked with selecting and creating sound effects that will enhance and add to the action taking place onscreen.

Music

For many, a movie without music is not really a movie. Music can emphasize a moment or draw emotion out of a scene. It can change a feeling of an existing scene, thus altering its meaning.

Although an entire song can be used throughout a montage sequence, music is usually used in the movie as a few bars or as a short theme.

Transitions between scenes are common places to use music. The timing of music must be customized for each movie, timed to moments known as ‘cues’. The director ought to have an idea of where his or her musical cues will be and what kind of music to use, or at least the style of music.

The director can then work with the composer to find the right emotional tone for each section of music in a reflection of what is taking place onscreen.

SUMMARY

- The first noticeable difference between a beginner’s film and a competent film is often good sound.

- A soundtrack contains four elements: dialogue, narration, sound effects, and music.

- The importance of music to the emotional impact of your film is grossly disproportionate to the relative investment of time and money. Do not take your music lightly or treat it as an afterthought.

Fast-Track Into 1st-Year Level Film Education

Made for Apple Books

Get beyond mere tips & tricks and how-to tutorials. This beautifully designed learning system is both a textbook and a structured course in one volume.

Learn from it. Teach with it. Gift it.