If there’s one argument on the set with repeat-offender status, it’s often about screen direction – and not just for newbies. Seasoned pros even get into it.

By Stavros C. Stavrides

Screen Direction

Once screen direction is established, it must be maintained in each progressive shot. This also applies to the direction our performers move, face, or look at, even when they are not moving.

When screen direction fails, actors can seem like they’re not facing each other in conversation, not looking at what they are supposed to be looking at, or instantly changing the direction of travel back to where they started. We could have one confused audience!

Now bear in mind, this is a rule. That means you may deliberately break it for the desired effect, such as in a montage. One filmmaker may break a rule knowingly to achieve an effect, another may stumble into it accidentally. Which would you rather be?

When Screen Continuity is misapplied, it can jar or confuse your audience, and really tee off your editor.

Axis of Action, Imaginary Line, 180-Degree Rule

Here’s a quick primer video:

So how do we keep track of screen direction while we’re managing the many aspects of a hectic production?

The Imaginary Line, or ‘Axis of Action’, or the ‘180-Degree Rule’ is the key tool used by filmmakers to maintain screen direction. It works like this:

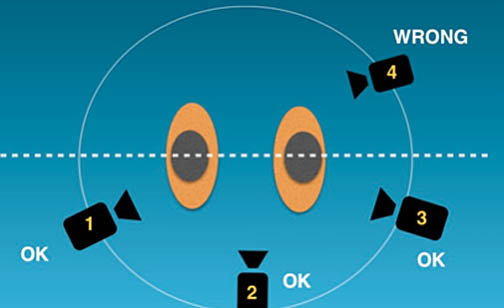

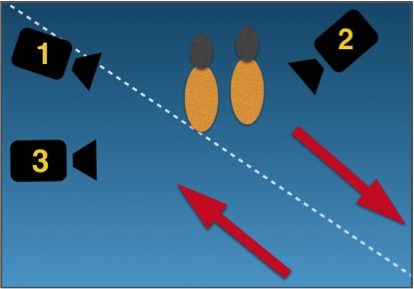

As we look down on the two subjects in this diagram, we draw an imaginary line through them, in the direction they move or face.

If all shots are done from one side of the axis (shots 1,2,3), they cut together with consistent screen direction.

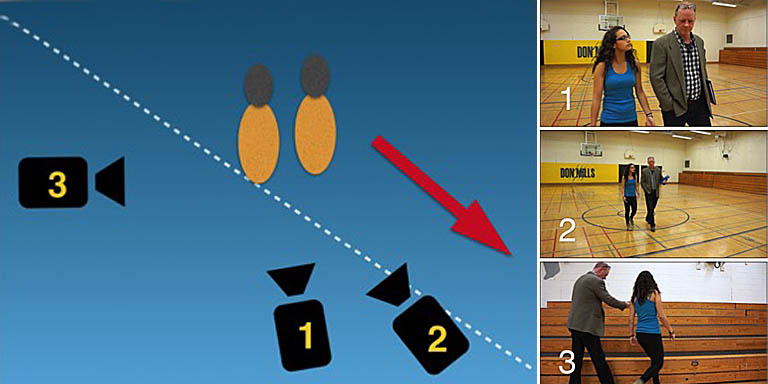

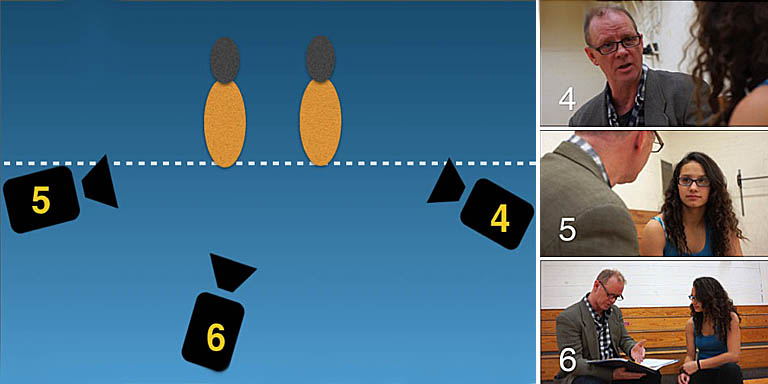

In the following example, a teacher and student walk and talk, then sit at a bench. This rule guarantees both screen direction and matching eye lines.

A Working Example

Shots 1, 2 & 3 are filmed from the same side of the imaginary line (the axis). Subjects move left to right in every shot. These shots cut together seamlessly, preserving a left-to-right walking direction.

Shots 4, 5 & 6 at the bench also stick to one side of the imaginary line. When shots are cut together, the eye lines will match. The actors appear to face each other instead of away.

When It Works:

When It Fails:

Shot #2 above steps on the ‘wrong’ side of the line.

When #2 shot cuts with the others, the subjects appear to change direction.

This article is a brief drawn from the ‘Screen Continuity’ chapter of

Cyber Film School’s MultiTouch Textbook

Remember:

Your subject is free to travel cross-screen, toward or away from the camera – directional movement will also always be intact as long as the camera doesn’t cross the axis.

In the following excerpt from our Book page, the clip from Boyz ‘n the Hood (1991) examines some tricky continuity when actors look off-camera and follow movement in the frame. Again, the camera stays on one side of the line, but subjects and their eye lines may freely move. Watch boy number two move his gaze in response to offscreen movement. Play this video a few times for a good study, and imagine how you would plan this coverage.

Can We Ever Cross the Axis?

The rule says you cannot, but as with many rules, there are loopholes. If we use one of the following techniques to avoid can avoid jarring the audience, we can smoothly cross the axis within the scene and resume coverage from the other side. Here are come ways to that:

Actor or Camera Crosses Axis

- You can cross the axis if any of the actors are seen changing screen direction within a shot. We then resume the rest of your coverage from that new side.

- Precede an axis change with a neutral shot. A neutral shot is one where the subject moves directly toward or away from the camera so that the sense of direction appears neutral – neither left nor right.

These techniques visually trick an audience, so we can use this lapse of screen direction to cross the axis and change screen direction on the next shot:

Here’s an example where an actor is neutral then changes direction in a shot:

Insert a Cutaway Shot

Cut to a cutaway shot, such as a couple sitting on a bench, a bird, or a stream. In the example below, it’s a dog. We then change the axis in the following shot, and shoot the rest of the shots from that side. This may be the most clever way to hide the fact you’ve crossed axis by mistake.

Alternatively, you can dolly or otherwise move the camera across the axis during the shot so the audience sees the move, then shoot the remaining shots on the new side of the axis. The camera actually crosses DURING the shot.

Now that we’ve been through the basics, there’s a lot more about screen continuity to cover in later posts, such as dealing with a meandering or zigzag path, talking through and moving through doorways, among others. But for now, keep this info in your pocket for that inevitable day you find yourself in an argument on the set. Or better still, share it for that “I told you so” moment. It could save everyone a whack of valuable production time – and headaches in the edit!