A film character’s screen dialogue should be written as a language to be spoken and heard, but many beginner screenwriters mistakenly write dialogue to be ‘read. It’s in the character’s speech where a screenplay can show off some mastery.

By Charles Deemer

Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

Updated October 25, 2022

For writers who aspire to stylistic brilliance of prose in models such as Henry James, William Faulkner, and James Agee, screenwriting can be a disappointing field.

That would be a bit like an Olympic runner joining the grade school track team. Strong writing skills in the traditional literary sense simply are not as important to a screenwriter as strong storytelling skills.

A minor exception, however, is the writing of screen dialogue. Writing dialogue is the primary area in which a screenwriter gets to show off a little mastery of language.

But dialogue for the screen is written in a special kind of language, and in my university classes, I am struck by how many students enter with no knowledge of this.

They are writing dialogue as a language to be read, when in fact dialogue must be written as a language to be spoken and heard. Those two universes are light-years apart.

People Speak in Fragments

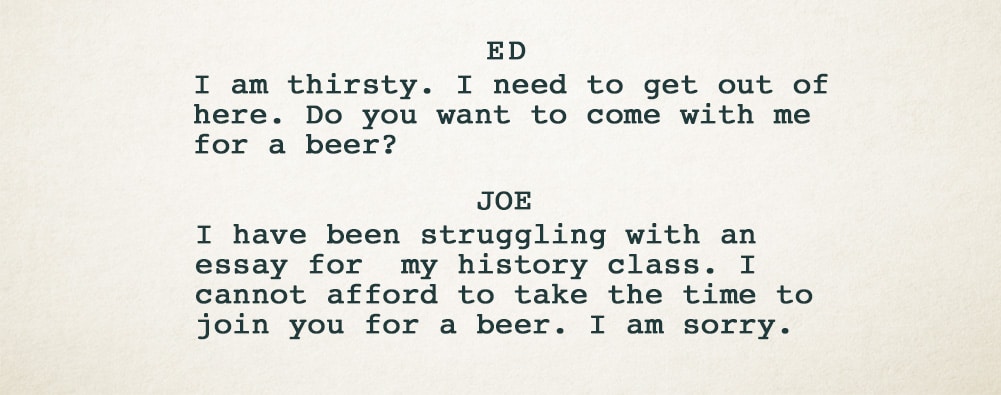

Picture a scene in which one student roommate asks another if he would like to go out for a beer. A beginning screenwriter might write something like this:

The above is poorly written for several reasons.

At the level of rhetoric, this language is too formal. The language we speak every day is much less formal than written language. Real spoken language is filled with sentence fragments and word contractions, the sort of things that are frowned upon by English teachers expecting formal written prose.

Ironically, often the better the student in terms of English literary skills, the worst the dialogue they write. That’s because they’re trained so strongly in writing formal prose which is seldom appropriate for dialogue.

A more informal, spoken translation of the above might be:

But we can still improve this dialogue by making it more personal, making it more of a revelation of character by giving it some “attitude”.

Screenplay dialogue must serve at least one of two purposes: it must either: Move the plot forward, or it must reveal character.

Give Dialogue An Attitude

How do we personalize dialogue? By giving it an attitude, in the sense that dialogue becomes a verbal imprint of individual character. Hence:

See the difference?

The first rewrite improves the rhetoric by making it informal, spoken speech, but the dialogue is still primarily informational.

In this second rewrite, we’ve infused the dialogue with attitude and wrapped the information in the point of view of the character. We begin to learn something about who the characters are by the way they speak.

“Lines with an attitude” is a good way to describe dialogue that reveals character, and it’s a major key in writing unforgettable spoken language.

Subtext In a Character’s Speech

In his book “Stein on Writing”, Sol Stein asks four questions of dialogue, establishing the conditions it must meet:

• What is the purpose of the exchange – does it begin or heighten an existing conflict?

• Does it stimulate [our] curiosity?

• Does the exchange create tension?

• Does the dialogue build to a climax or a turn of events in the story or a change in the relationship of the speakers?

Stein also notes how interesting dialogue is often oblique. He gives many examples in his book. One is this (boring) exchange:

“How are you?”

“Fine”

A boringly ordinary exchange, right?

But when we change to:

“How are you?”

“Oh, I’m sorry, I didn’t see you.”

we create interest because the person does not answer the question, but establishes subtext – something more than meets the eye is going on here.

Ordinary speech is boring, and good dialogue is carefully crafted to give spoken exchanges tension and mystery, direction and conflict. What is not said directly but nonetheless communicated is “subtext,” meaning under the literal surface of speech.

A pejorative term for poor dialogue that has come into fashion is “on the nose” dialogue, which is the opposite of dialogue. Russin and Downs define it this way in their book “Screenplay: Writing the Picture”:

“When a character states exactly what he wants it’s called on-the-nose dialogue. The character is speaking the subtext; there is no hidden meaning behind the words, no secret want, because everything is spelled out. But most interesting people, and certainly most interesting characters, don’t do this.

~ “Robin Russi, William Missouri Downs

Example of Subtext

Below is a very simple scene from David Lynch’s movie “The Straight Story” written by John Roach & Mary Sweeney. It’s an excellent example of subtext:

Before Alvin begins his incredible journey riding a lawn mower across the country to visit his distant brother, his daughter Rose goes to the grocery store to buy him supplies.

Rose is fearful about her father’s trip. Notice how Rose’s feelings of grief and fear transfer to a simple grocery item, a braunschweiger sausage.

Yet this scene is not about the Braunschweiger, but about her anxiety over her father’s trip.

Rose takes items to the counter. Brenda is the checkout cashier.

The most ordinary everyday settings such as a checkout counter can serve as an arena for revealing emotional material.

And such a scene doesn’t take very much time at all when handled by a skilled screenwriter, so every line works. The focus is tight, and that idle chit-chat doesn’t dilute the scene’s energy.

In the hands of an amateur, this scene could be disastrous, full of small talk that goes nowhere.

Here the progression is logical, direct, concise and efficient, all moving toward the unspoken but evident “punch line,” in which the subtext is:

“I hate that my Dad is going on this trip!”

When you write dialogue with subtext, you are letting the audience discover meaning through the heart before they understand it through the head.

Expository (obvious and overly factual) dialogue aims at the head, at understanding.

Subtext, on the other hand, aims at the heart – at feelings.

It is more powerful writing to make your audience feel first and understand second.

Summary

Here are some things you can do to improve your skills at writing dialogue:

Read your script aloud! The written word is not the spoken word. Even better, get your script into the hands of the actors. By doing a “staged reading” of your script, your ear will tell you what your eye will miss when it comes to poor dialogue.

Listen to the speech of people around you. On the bus, in a restaurant, at a party. Listen especially for idiosyncratic rhetorical patterns that you can “borrow” and adapt to your work.

However, do not make the mistake of believing that “real speech” is the goal. Dialogue is always crafted – it is, in fact, more interesting than real speech (usually) but gives the illusion of being real speech.

Write with subtext. People normally don’t speak as directly as characters do in a soap opera. Let them speak obliquely, around their true emotions, so that the listeners/audience will discover meaning through feelings, through the heart.

When you write dialogue with subtext, you are letting the audience discover meaning through the heart before they understand it through the head.

Rewrite your dialogue and read your script aloud again.

More Free Articles

We publish an interactive Apple Book, a structured film program based on leading 1st-year film programs.

More Info