Writing Assignment: Build the Character

This screenwriting assignment helps build the character’s off-screen life. Before you write, imagine details that not only appear on screen but also their unseen life, which will inform the character’s response to circumstances as you write.

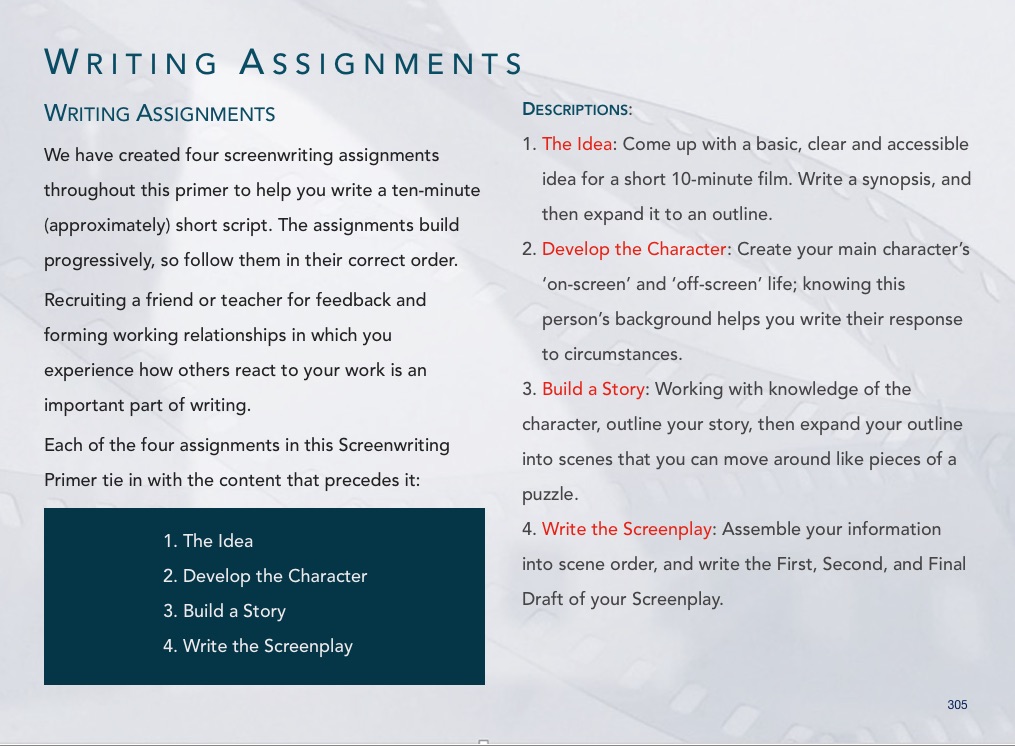

This assignment is drawn from “Develop the Character”, one of four assignments in the Screenwriting chapter of Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook.

Inside:

Page 306 Screenshot

Defining The Character

Characters sometimes show up fully formed and shout, ‘Here I am!’ At other times, they are elusive, taking ages to feel real, or at worst, become dull and uninteresting very quickly.

Some writers believe that the easiest way to develop a hero is to put them in a place where they must make decisions that reveal their character. Others think that keeping them actively engaged with others reveals who they are.

Then there are those who rely on having the character heavily narrate to us what they are thinking.

All of these approaches are valid ways of developing a hero and all principal characters, but no single approach is sufficient.

Get to Know Your Character Before You Write

Get to know their passion or obsession; most heroes of a story have a goal, a need, and an intense desire.

Let’s start with what motivates this person:

- What do they want more than anything else in the world?

- What is this person willing to give up to get it?

- Is your hero actively pursuing something or forced to react to a circumstance, such as running from or avoiding something or someone?

All good drama develops out of character so get to know your character intimately.

Start a Journal or Notebook

Start a notebook or journal just for character exploration. Label a page with the name of your main character, or hero. Add another page for each key character your protagonist hero interacts with, such as Antagonist, Romance, and Reflection.

Flesh out your main character first, both in the movie and in their life outside of the story. Begin to imagine and note the following:

The Average Day of This Character

- What gets them out of bed in the morning?

- Do they set their schedule or do others dictate their time?

- Do they have a job or are they self-employed?

What Your Character Looks Like

- Physical description.

- How do they typically dress on a casual day? On a work day (if applicable)?

- Does their physical size and shape affect how they feel about themselves?

- How do they carry themselves? Do they slouch and shuffle, or are they bold and confident? And does this demeanor change between situations and interactions with others?

The Daydreams that Get Them Through The Day

- Are they trying to pursue those dreams?

- Are they eager and motivated or have they lost their drive, living in ‘wish’ mode?

- Are they in love?

- Are they searching for something?

- Are they at home where they are, or are they a foreigner to this place?

- Do they sometimes get depressed?

- Is there a particular passion or hobby they have? What makes them memorable?

Remember: If you choose to show these cues visually, do so through their actions and interactions, before revealing them in dialogue.

Relate these details to your story

Once you have worked on your list:

- Try to imagine where your main character has come from just before your story started.

- What will happen to him or her after your story ends?

- Why would these parts of their life most interest us?

Characters ‘0ff-screen’ life

Part of what helps build character is understanding the story behind the details, even if they’re not revealed in the script. Examples:

- A particular tattoo and the reasons behind it.

- An instrument that plays when the character is sad.

- The hero’s relationship to a particular animal, landscape, song, artwork, etc.

Repeat this process for some of the secondary characters in your script, but with less intensity.

Try to understand:

- What drives or motivates each character.

- What makes them happy.

- How they influence your hero.

- Decide what role they will have in the development of the story.

Remember: Many of these details about your character may never appear in the movie. They help to more fully understand your characters, thus enabling you to richly write about them with more substance and authenticity.

This article is reproduced from the Screenwriting

Chapter in Cyber Film School’s

Multi-Touch Learning System