Fight all you want about the meaning of Premise vs. Theme, and why not? It seems every smart-aleck picks a fight over what these words mean. Truth is, it’s not that complicated. Welcome to the smart money.

Stavros C. Stavrides

Premise & Theme Defined

Let us show you how effective screenwriters use Premise and Theme when writing their screenplay. We did not invent the definitions of Premise and Theme as described here –many great film schools teach it this way. But we think that it sure simplifies things. So let’s get started.

Screenwriters approach the task of writing in several ways. Some are inspired by a sudden idea driven by a central character and situation. Others want to work in a genre they love, like science fiction, action-adventure, or horror. Yet others are preoccupied with a strong concept or wish to illustrate a point about society by sending a strong message.

Whatever gets you started on your screenplay, such a motivation can be the foundation of your work.

Premise and Theme Arise From the Creative Process

As you lean into your story, what arises from the creative process is a complex weaving of Premise and Theme, two aspects of a story you become aware of as you create your story.

The film industry has more than a few definitions of premise and theme within the film industry. In this book, we put it quite simply. Let’s look at the Premise and Theme of The Godfather (1972).

PREMISE: The idealistic son of a powerful Mafia crime boss returns a war hero with no interest in the family business, but tragic circumstances pull him into a mob war that could tear his family apart.

THEME: “You cannot avoid your destiny” or, “Family comes first “sharing its success and its downfall”

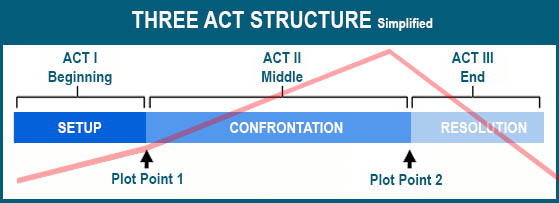

Premise: the “What If?”

The premise sets up the main characters’ characters, circumstances and challenges. It’s often presented as a ‘what if…?” proposition.

The premise becomes evident early in the process as you flesh out the characters, their circumstances and conflicts – the ‘what if…but’? For example, “Jaws” (1975):

What if a beach-town cop wants to stop a killer shark at the height of tourist season, but as deaths pile up, the greedy mayor blocks him for the sake of tourist dollars?

Theme: “What’s It About?”

The theme speaks to the film’s overall moral or lesson it teaches – the overall message. Jaws (1975):

Public good vs. criminal greed

Where the premise of your story likely comes early as you plan and execute, your story’s theme may reveal itself at any time in the process. You may know the theme upfront, or it speaks to you later as you “dream your movie”.

In the following clip from Cyber Film School’s Filmmaking Textbook Screenwriting Chapter: Gerald DiPego talks about a story’s Theme:

Don’t rush the theme – it will emerge. Themes can change as you go. More than one can appear, but once the main theme is clear, it should reverberate in every page and every scene of the script as you polish and rewrite it.”

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.