In Writing Action – Part One, we showed “What To Write“, the first of three decisions involved in how to write the action portions of a screenplay. Here in Part Two, we show how top screenwriters format action in filmic beats without insulting the director.

By Charles Deemer

Edited by Stavros C. Stavrides

UPDATED December 7, 2022

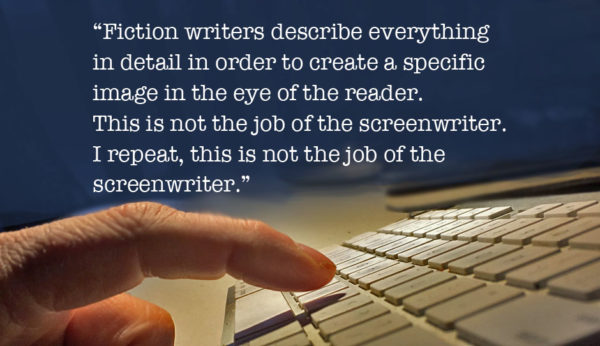

Show, Don’t Tell

In Part One, What to Write, I showed how the screenwriter’s task is to write what is seen on the screen, not in the extraordinary detail of literary fiction as many beginners do, but simply and directly for the screen.

But there’s another common beginner mistake when writing action. Like fiction novelists, they get inside a character’s mind.

Further down, we reveal how to use ‘white space’ to subtly ‘direct’ the film’s action.

Consider a scene that starts like this:

INT. APARTMENT – NIGHT

Joe opens the door and turns on the light. He steps into the room. He senses that someone has been here. He wonders if he’s been robbed or what. He rushes to the bedroom.

Although we write the action literally as if we are watching the movie unfold before us, notice some flexibility here. When we say “He wonders if he’s been robbed,” it’s not direct action, but the subtle difference is important. It allows room for the actor to show it. There is some flexibility here, to be sure.

For example, one might write: “He looks puzzled and disturbed. Has someone been in his apartment? He rushes to the bedroom.” Such a subtle question clarifies the motivation, in the present time, for the previous description and serves as a clue for the actor.

What we try to avoid is expository information in the action element that is not communicated on the screen through either action or dialogue. For example:

Sam sinks into the couch and opens the divorce papers. He’s been married to Helen for fifteen years. He reaches for the phone to call his lawyer

Sam sinks into the couch and opens the divorce papers. He’s been married to Helen for fifteen years. He reaches for the phone to call his lawyer.

The audience cannot know how long Sam has been married, nor can we yet see that he’s calling his lawyer. These are not said in dialogue nor demonstrated in the action or visual cues. Your audience is not the reader in this sense, but the person WATCHING THE MOVIE.

Always be aware that you are writing a blueprint for a movie, not a literary document. You therefore must accept many more writing restrictions than those found in other forms of writing such as novels.

This post is a support article for the “Screenwriting” chapter in Cyber Film School’s

Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

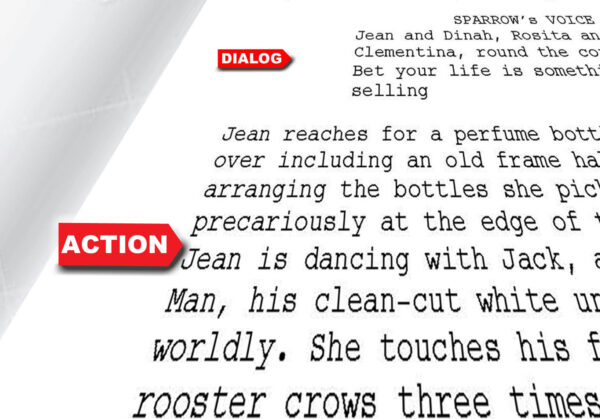

Break Up Action Into Visual Beats

In the old days, writers used technical jargon like shot sizes, angles, and camera moves in their scripts. As we reveal in “Making Sense of the Screenplay Format” this practice has long been verboten.

Yet the screenwriter has a very powerful tool in the way he or she places action on the page. It’s simply called ‘White Space.’

Few beginners write as if they are aware of this – even many experienced screenwriters fail to apply this element of screenplay craft.

White Space

We consciously use “white space” to direct the movement and include the visual cues of your story.

The way you define your paragraphs in your action element determines how white space appears on the page, and this has subtle but important consequences.

Again, let’s look at an example. Here’s an extended action sequence as many beginners would write it.

Many beginners would write the following sequence as one paragraph:

Sally comes outside onto the porch, closing the door behind her. She tests it to make sure it’s locked. She looks in the mailbox and takes out the mail, putting it in her purse. She walks down the steps and to her car in the driveway. She unlocks the door and gets in. She gets out again and goes back up the steps and puts the mail back in the mailbox. Back to the car, where she starts the engine and backs out of the driveway.

Although the exposition is technically direct, experienced screenwriters use white space to break down the action into several beats, as if each action is one visual setup. We are in a sense “directing without directing.”

Here is the above paragraph again, but now broken into beats for every distinct action.

Sally comes onto the porch and closes the door. She checks that it’s locked.

She takes the mail out of the mailbox. She puts it in her purse.

She walks to her car in the driveway. She unlocks it and slides in behind the wheel.

She sits. Then she gets out of the car.

She goes back to the mailbox and returns the mail.

She returns to the car and gets in. She starts the engine.

The car backs out of the driveway.

Clever, huh? Notice several things:

By breaking up the paragraph into seven short paragraphs like cuts in a movie, we’ve isolated each of the visual beats of the sequence.

By no means are we ‘directing’ this film in shot sizes, angles, and camera moves. We do in fact suggest in a very subtle way, the individual action beats.

We break up the action by ‘cutting’ from beat to beat with considerable white space on the page, making it more inviting with a much easier grasp on the pacing of the scene.

Shane Black (‘The Predator’, ‘Iron Man 3’) has noted that action in a screenplay needs to have a sense of being read vertically as if the film is running down the page, rather than horizontally across the page in the usual fashion of reading.

“Pearl Harbor” Example

The key to good action writing is clarity and simplicity with strong visual elements that define a scene in distinct beats.

Let’s close with this stellar example, from Randall Wallace’s celebrated action sequence in “Pearl Harbor”:

EXT. PEARL HARBOR – DAY

The harbor lies quiet. It’s a sleepy Sunday morning. Children are playing, officers are stepping from their houses in their shorts to get the morning paper…

EXT. MOUNTAINSIDE – OAHU – DAY

Hawaiian Boy Scouts are hiking on a side of one of the mountains overlooking Pearl. Suddenly booming over the mountain, barely ten feet above the summit, comes a stream of planes.

The boys are awed. What is this?

EXT. PEARL HARBOR – DAY

QUICK INTERCUTS Between the approach of the Japanese planes, and sleepy Pearl Harbor…

— The planes, in formation, their propellers spinning, their engines throbbing…

— Pearl Harbor, with the ships silent, their engines cold, their anchors steady on the harbor bottom.

— The Japanese submarines heading in.

— The American destroyers docking, instead of going out to search for them.

— Another formation of Japanese bombers climbing high, into attack position.

— The Japanese torpedo planes drop down to the level of the ocean, their engines beginning to scream.

— The American planes bunched on the airfields.

— ON THE JAPANESE CARRIERS, Yamamoto and his staff huddle tensely, over their battle maps.

— ON THE JAPANESE CARRIER DECKS, the second wave of planes is being brought up and loaded with munitions…the Japanese flag snaps tautly in the wind…

— ON THE GOLF COURSE NEAR PEARL HARBOR, American officers are laughing on the putting green near the clubhouse, where the American flag droops from the flag pole, limply at peace.

— The Japanese planes roar down just over the wave tops of Pearl Harbor itself.

— Children playing in the early morning sun, looking up as they see the planes flash by. The children look.

— they’ve never seen this many, flying this low…but they are not alarmed, only curious.

The images come faster and faster, the collision of Japan’s determination and America’s innocence

See the distinct beats? They read like a movie: Action. Cut. Action. Cut.

It’s subtle, but it serves up a visual story while not interfering with the director’s interpretation of every beat.

This is action writing at its best!

Making Sense of the Screenplay Format

MORE GREAT SCREENWRITING ARTICLES

“Writing Action — Part Two” Copyright © Charles Deemer. All Rights Reserved.