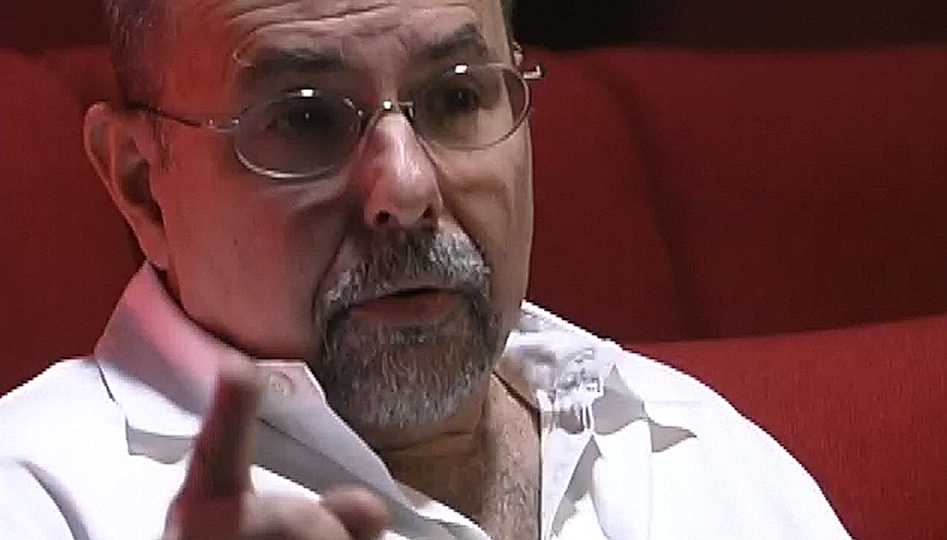

The long and the ‘short’ of it with Two-Day Film School guru Dov Simens

We had the pleasure of interviewing filmmaking Two-Day Film School guru Dov Simens some years ago for Cyber Film School. What a gas! He’s bigger than life, a straight shooter, and what you see is what-you-get with this guy.

by Stavros C. Stavrides

Dov breaks down the filmmaking process, from script to production as a system based on a formula.

For example, “Don’t let anyone tell you screenwriting is not a formula,” he says. “Screenwriting is a formula. We took it off of Shakespeare. Shakespeare took it from Marlowe. Marlowe took it from Plato. Plato took it from Aristotle. And I guarantee you Aristotle took it from a caveman!” He’s proud to teach.

Love him or hate him, he’s had some interesting names walk through his doors before they became household names (well, at least in a filmmakers household – for the filmmakers who have houses) – Quentin Tarantino, Chris Nolan, Spike Lee, Kevin Smith, Queen Latifah, Guy Ritchie, among others.

He spells out his formula of feature filmmaking as he sees it. He advises that if you’re going through the trouble of hiring gear, actors, or a location, may as well do a feature – not a short film. Here we have his seven-minute-eleven-second hell-raising tirade that is his formula. If you dig his drill sergeant manners in these few minutes, imagine a two-day power weekend with Dov Simens!

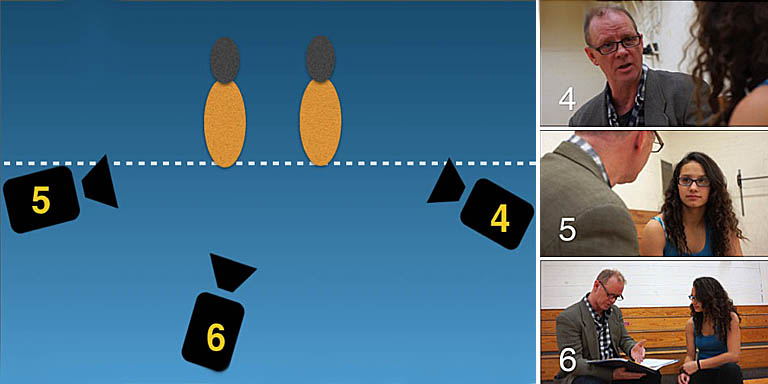

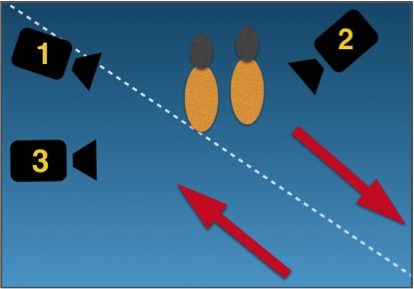

We shot this interview some time ago – so his references to distribution revolve mostly around theatrical markets. Otherwise, Dov’s advice is timeless.

We had so much fun hanging out with this guy. Please leave comments below so we can kick around his ideas, for better or worse. Do you agree with his approach? Is filmmaking a formula?

“Stop being scared of the word feature!”

You can visit Dov and explore his program at webfilmschool.com

*This link is provided for informational purposes and as a courtesy. Publisher of this post does not receive compensation, nor is it an endorsement.

Ahead

- Rhythm & Pacing

- The Screenwriting Formula

- Getting a Name Actor

- Theatrical Distribution

- The Production Formula

TRANSCRIPT:

It’s so dumb! I’m going to be the only teacher in the world that’s ever going to say, “Don’t do a short. Don’t do a short!” Does anybody buy shorts, that writes checks? NO! So your first business decision in the film industry is to make something that you are guaranteed not to be able to sell. Stupid!

Now let’s stop being scared of the word “feature,” but let’s do a feature that you can handle, which is a dressed up stage play, a courtroom drama, a one-room location. I jokingly in my class say, for the first feature film, “Here’s your formula. Take twelve kids to a house and chop them up. That you can handle. You know, it’s possible that will get out there. And there’s not one of you out there listening right now to this that can’t get a camera, can’t get some film or tape, can’t get twelve actors that are called waiters, put them in a room and tell them to talk for 90 minutes. Hit the “ON” Button.

Learn Rhythm and Pacing

“It takes about four or five scripts.”

The sole single biggest problem of first-time filmmakers had never become a second time filmmaker is they fall in love with the first typing that comes in front of their face, especially if they typed it themselves. They all believe they’re instantly Michael Jordan the first day they pick up a basketball. And in the film industry, in the writing industry, we believe even if you’re gifted about writing, you don’t really learn how to write the great script until your fourth or fifth script.

You got to learn the rhythm, learn the pacing. You can learn the formulas from the books. You can learn how to type from the books. But somehow the rhythm you can’t learn. It just happens. You got to play a little basketball for a while. You got to rehearse, and it takes about four or five scripts.

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.

The Screenwriting Formula

“I’m the blatant film instructor that cuts right to the chase.”

And the screenwriting instructors that are out there – Bob McKee, Syd Field, John Truby, Michael Hauge, Linda Seger, Viky King, Madeleine DiMaggio, they’re all very good. They give intensive one-day, two-day, three-day classes, etc. And they all talk around the Hollywood formula. They’re all paranoid about saying it’s a ‘formula’, screenwriting. They all swear it’s not a formula ‘cause god bless, some critic might criticize them for teaching formulaic screenwriting. And they all then teach a formula and they swear it’s not a formula, and they’ve all created little pseudonyms for what this is –‘paradigm,’ ‘inciting moments’, ‘plot points,’ whatever.

Well, I’m the blatant film instructor that cuts right to the chase. I’m gonna tell you right up front: screenwriting is a formula. We took it off of Shakespeare. Shakespeare took it from Marlowe. Marlowe took it from Plato. Plato took it from Aristotle. And I guarantee you Aristotle took it from a caveman.

Now you want the formula? I’ll give it to you. I’m proud to teach! I’m proud to be the great teacher, and here’s the formula:

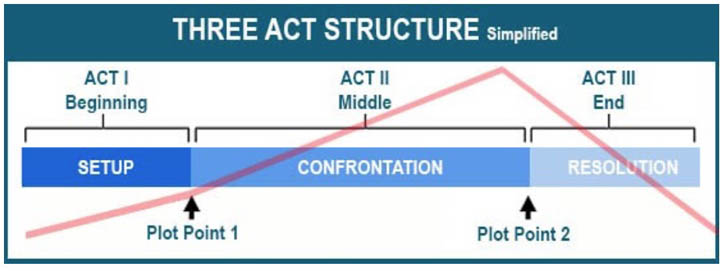

Every screenplay that’s great has 5 “uh-oh’s”, “Oh shits!” and one “Oh my god!” in it – 5 “uh-oh’s”, “Oh shits!” and one “Oh my god!” in it.

There are 40 scenes in a movie maybe there are 50. You got your rollercoaster ride that’s built in there:

- Introduce the boy

- Introduce girl

- Introduce the situation

- Introduce the desire

- Introduced they want to take an action

- Introduce they take an action

Everything seems to be good and now, UH-OH!” We’re only about 8 to 10 minutes into the movie. Pull the carpet out from underneath them

Two scenes later give them a further complication called an, “Oh shit!” But we’re only about 12 to 15 minutes in the movie.

“Uh-oh! Oh shit…Uh-oh! Oh shit…Uh-oh! Oh shit…”

And then, “Oh my god! No way will they ever get through it!”

Two scenes later it gets resolved.

Getting a Name Actor

It’s very important to have a name attached to your project. You’ve heard that ten thousand times. It’s very important to get a name attached to your project. But to get the name attached to your project you don’t have the check to pay it on your first project, so it’s ridiculous stuff. But when you get to your third feature film…If your first feature is a no-budget feature film that gets out there gets to the proper festival, gets picked up by a distributor, they will do creative bookkeeping, but they’ll make you famous and you probably won’t make a penny from it.

But then on your second film, now you’re gonna get a salary upfront a higher budget and you get a little bit of money in your pocket, you make your second film. And if your second film gets out there and makes money, now enough of the names! (If) the industry found out that “that guy or that woman is good, I want my name attached to their project because they’re going to take me to another level and they’ve proven they can make money,” then they’ll come to you.

Theatrical Distribution

“The best thing about you is when you’re done you’re broke!”

Distribution. If you can’t distribute you got to distribute and you’re not gonna distribute. Stop this dribble with this self-distribution crap. (If) you take your film, make a bunch of prints, put them in Edmonton, put in Calgary, put them in Toronto, put them In Denver, put them in Miami in a small theater, you’re gonna be in small claims court in every state in every city In North America trying to collect from theater owners that are close to broke. And if they ever do pay, you take six months before they ever pay you, so yes you need a distributor. You need a distributor.

You’re not going to get the major distributors – Warner Brothers, Paramount, 20th Century, Universal, but each one of the major distributors has a mini-major arm that’s smaller than a Miramax or New Line which is good also. A Strand Releasing, a Fox Searchlight, an Orion Classics, Sony classics. Now where are you gonna get this distributor? You know what? You’re gonna go to film festivals. You take your film and go to a festival. Every city in the world has cultural events, opera, ballet, symphony, the last thing is a Film Festival. So they need your film. But understand the film festival will charge you entrance fees, submission fee, projectionists, and booking the theater.

Why do you go to a festival? Every distributor in North America is making their own films themselves, but they know there are people out there like you, quote “independent filmmakers” that are dumb enough and stupid enough and naive enough to spend your own money. So obviously distributors are looking for you. You’re free! Do you know why distributors love you? You’re free. You’re cheap. You have no overhead, no guild or union affiliations, no development cost, and the best thing about you is when you’re done you’re broke!

The Production Formula

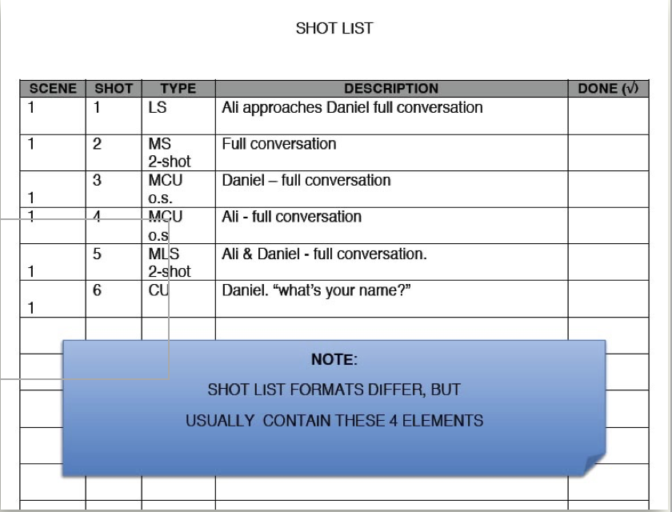

Get the script. How much money do you have? How many weeks can you afford to shoot? You can afford one week of shoot, that’s actually nine shooting days. Monday you rent the camera and the equipment over two weekends. You got a 90-page script, you got ten shooting days. That’s your shooting schedule.

(If) you got enough money for two weeks to feed a crew and pay your crew and rent the equipment for two weeks, you got 13 shooting days. Divide 13 into 90 pages, that’s a script – that’s 7 shooting (pages per) day. You got enough money for three weeks? That’s 18 shooting days divide that into a 90-page script, 5 shooting pages per day.

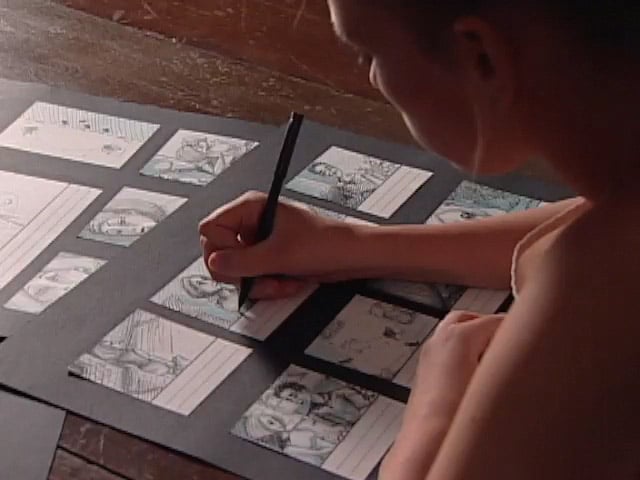

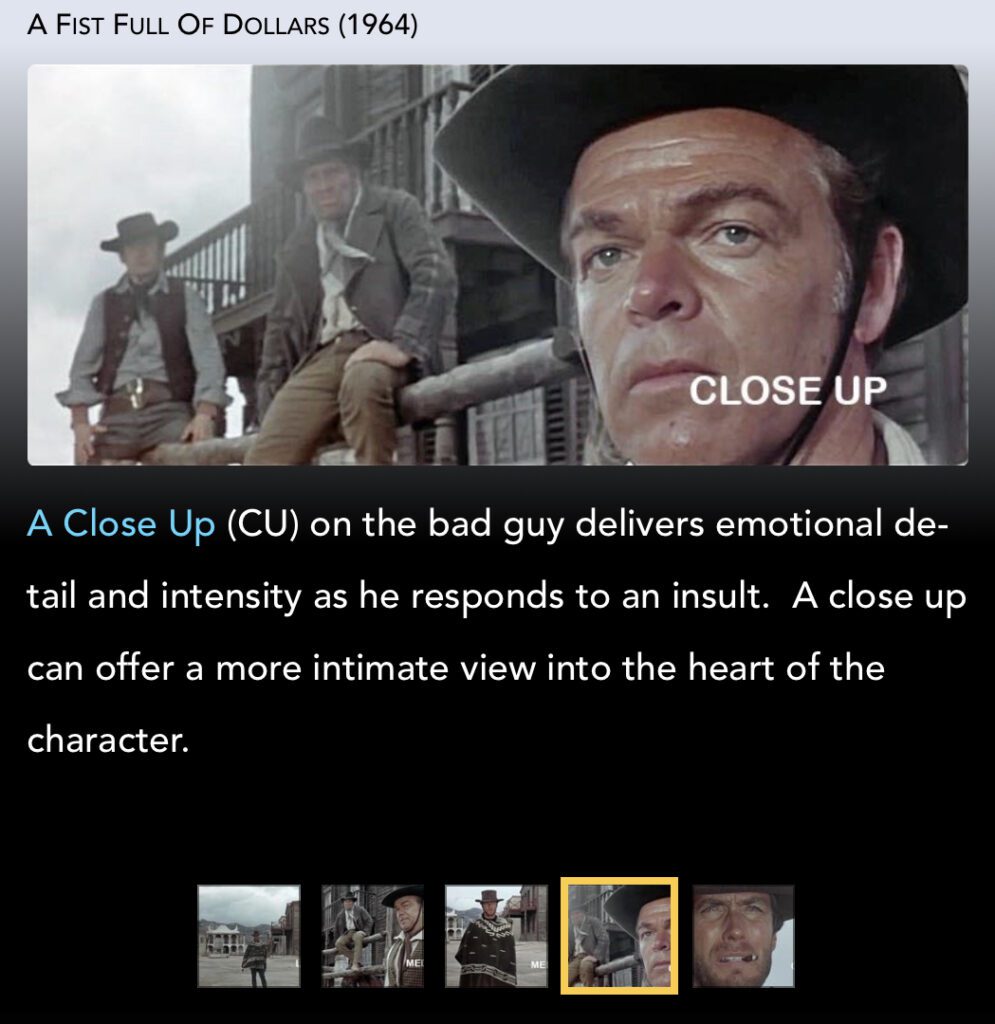

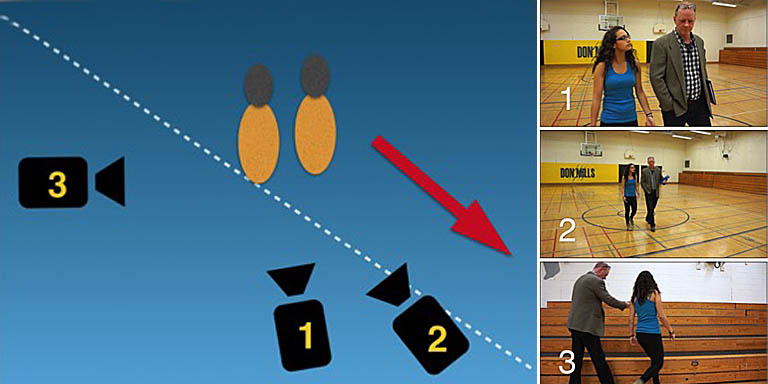

Five pages per day, you got approximately 12 hours of shooting daylight in the day, let’s take two hours for eating and getting ready. 10 hours of shooting, so five pages – one page every two hours. And in those two hours, I want a master shot, two medium shots, a reaction shot, a point-of-view shot, a cutaway shot, and a cat-in-the-window shot. So you got 18 to 20 minutes for each shot. On each shot, I want key lighting, backlighting, fill lighting, and possibly an eye light. And I don’t want the camera just on a tripod. I want it with some dollying and some little bit of camera movement, and “let’s go!”

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.