A valuable exercise in the development of your story is getting to know your characters. The definition and development of character is one of the central concerns of the writer. Their motivations are what drive the story forward. If you don’t know who your characters are, you don’t know why anything in your story is happening, and you are lost.

Contributed By Glen Berry, Edited By Stavros C. Stavrides

Important Concepts

- Create “Real” Characters

- Find your character’s motivation

- Character Arc is the heart of the story

The Back Story

In a feature-length project, we have some time to develop character. In a short film, it is much more challenging. We must be very utilitarian with the words on the page to draw out an interesting character.

Often, the details about your characters may not even be exposed onscreen, but are the most important factor in making them rich and full and believable. Ask yourself:

- What do they look like?

- Into what social standing were they born?

- What is their philosophical position?

- Are they religious?

- What phase of life are they in?

- What events have shaped their lives up to this point?

- Have they led an extraordinary life? Have they travelled the world?

- Do they take risks?

- Can they maintain a long-term relationship?

- What are their personal quirks and traits?

Answering these kinds of questions is the background work necessary to create a complete character. You need to know many things about your character outside the framework of the story (the back story) to understand what happens inside the story. A clear idea of the character will translate to the page. It will be easily understood by a competent director or actor. If your idea of the character is unclear, it will also be unclear to the actors when they try to work through the lines and understand who it is that they are portraying.

The Environment

Research is the key to finding the details to wrap around your characters to make them three-dimensional people. Know your setting, the environment in which this person lives, even if it is imaginary.

The environment will shape the person and allow you to dig into the development of their psyche. Think about the actor that will have to portray this character, to be believable in these imaginary circumstances you set up. It must be clear who the characters are and what drives them forward.

The Protagonist

Every story has a protagonist, the main character, and usually a hero.

If a person stands in the way of the protagonist, they are called the antagonist. In the classic sense, the antagonist is the ‘bad guy’. It is the differences between the antagonist and the protagonist that provide telling information about the protagonist’s character.

The antagonist and the protagonist maneuver in a push-and-pull dynamic that results in conflict, which drives our plot forward. We have many types of conflicts that drive our story forward, it could be human vs. human, human vs. society, human vs. nature, human vs. the supernatural or human vs. him/herself.

No matter what the approach, you must still identify the protagonist and what motivates them to discover the heart of your story.

This post is a reformatted section from the chapter “Screenwriting” in

Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook.

The Character Arc

The protagonist has an objective to obtain and an internal drive to obtain it. The way we learn about the protagonist is what they are seeking, how they go about the search and how they handle obstacles put in their path.

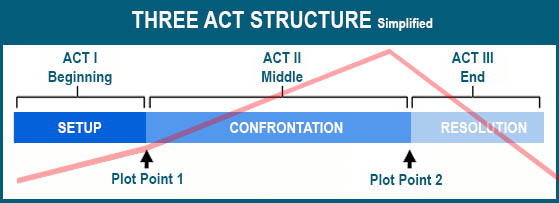

This is commonly described as a character arc. Like the dramatic curve, characters go through a transformation over the course of our three acts.

The protagonist, in particular, is going to have highs and lows as they move through their struggles to overcome obstacles and resolve the conflict that they face. By the end of the story, the protagonist will be changed in some way by the events that transpire.

We ourselves are shaped by the events of our lives, and so are our characters.

Such changes can be positive or negative but it is the effect that events have on the behavior of our character that demonstrates to the audience what it is that we are trying to say.

If the protagonist meets with failure, why do they meet with failure:

- How does it affect them?

- Does it destroy them or make them stronger?

- Does success yield happiness?

- If it does not, why not?

And if the main character does not change at all, what does that say about them and their life? In these questions, we will find the heart of our story.

The Hero’s Not Always Good!

A common mistake in character development is to assign the protagonist all good traits and the antagonist all bad traits. This is a device of comic books and Kung Fu movies and although entertaining, it does not make for a believable character.

We all have weaknesses (as we dare to admit). Our frailty, or dark side, makes us more human, and more believable. If you do not have a believable character, there is little authenticity for the actor to grab onto.

Real life is not so simple – there is no such thing as all-good guys and all-bad guys. Although difficult, introduce some vices to your knight in shining armour and some virtues to your wicked stepmother.

It is the natural tendency of the audience to identify with the protagonist. Giving him or her some flaws will make that character more sympathetic, particularly if the antagonist exploits those weaknesses. Have no fear; your protagonist can absorb a great deal of trashing before he or she is sullied in the eyes of your audience.

The Anti-Hero

This interesting effect gave rise to the anti-hero popularized in several of the Spaghetti Western Clint Eastwood films where the protagonist is nearly indistinguishable from the antagonist in character.

The Good, The Bad and The Ugly is an excellent example of the anti-hero. In one scene, the protagonist dissolves his partnership by leaving his companion in the middle of the desert without water to die or be captured and executed.

What makes a protagonist that would behave in such a way the ‘good guy’? That’s the kind of question that draws in the viewer instead of boring them with clichés.

The distinction between good and evil can be so subtle as to be nearly indistinguishable. It is in those small differences we find the difference between a good person drawn into the evils of the world and a person who has given themselves over to evil acts.

It is a fine line to ride. Strive to create an imperfect and real character that challenges the viewer’s notions of right and wrong, yet allows them sufficient justification to believe in their good traits and intentions.

The audience will identify with the main character if you give them half a chance and they will excuse his or her flaws and sympathize with their struggle.

The Foil

A story-telling device that often proves useful is that of the foil. The foil is the friend or companion of the protagonist that is great, but not that great.

The purpose of the foil is to make the protagonist look good. The foil is often a likeable and charismatic sidekick.

The foil is never far from the protagonist’s side but lives constantly in his shadow. The death of the foil at the hands of the antagonist is commonly used as the spark that sets the protagonist in motion to the final confrontation, which we will discuss in more detail later.

Less is More

When establishing your cast of characters, remember that less is more. You only have enough time to develop so many characters who have a meaningful role in your story.

The audience will only care about a few, so make your choices well. Combine characters where possible to focus your attention and the attention of the audience on as few people as possible. It’s no mistake that films with large casts tend to be sweeping epics. Character development takes time.

When you are creating a short film, you have very limited time to introduce characters and develop them. Focus on your protagonist. They will be the star of your film and the agent of your concept. Be very mindful of any character development that does not revolve around your protagonist.

Summary

- The concept of your screenplay should be reducible to a few sentences. Without this clarity, you cannot build a story.

- Invest time in determining how your concept is different from others and how it might be the same. This will save you from unwittingly remaking another film.

- Many independent films suffer from a lack of clarity, which can almost always be traced to poor structure. Breaking from convention is encouraged but if the result is confusion, look at your story structure.

NEXT>>>

SCREENPLAY FORMAT

The importance of a properly formatted screenplay

<<<PREVIOUS

STORY STRUCTURE

The importance of a property formatted screenplay

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.