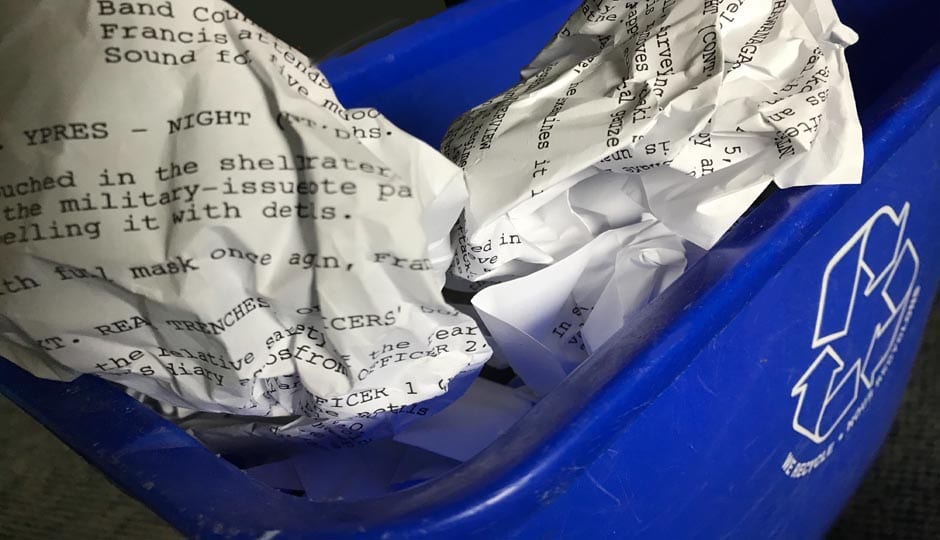

What beginning writers often forget, blinded by their insecure craft, is that “being bad” is a legitimate part of that process. Even first drafts from famous authors like Faulkner, Steinbeck, and Hemingway were ‘bad’. It’s liberating to know that the best writers in the land wrote drafts that needed tons of rewriting.

by Charles Deemer

Edited bt Stavros C. Stavrides

- Read with a fixed eye on flow & character

- The chainsaw is your friend

- Crank it up

Reading with a Fixed Eye

The rewriting process begins with careful re-readings of your draft. I suggest a quick read first, just to see how the story flows, and then a series of more careful readings, each focusing on a particular aspect of the draft.

Begin the careful readings with a focus on the main character. Is, in fact, the protagonist ALWAYS the focus of the story?

Often in beginning scripts the main character “disappears” in Act Two. The character simply may be absent for pages at a time – I get nervous when my protagonist is not in a scene for five consecutive pages.

Other times the protagonist is around but too passive, others are doing everything. At still other times some other character proves to be far more interesting than the main character (evil characters often steal the stage this way).

Make sure your script follows the main character on “a journey” through the story: that the protagonist is always front and central, that the journey moves into situations of increasing jeopardy, that the pace quickens into a rush through Act Three, and that the protagonist grows from the journey.

This is a free support article for Cyber Film School’s Multi-Touch Filmmaking Textbook

The Chainsaw is Your Friend

The next thing to look at is script economy.

First, look at your scene design: when do scenes begin? when do scenes end? Typically, in a first draft, there will be scenes that begin too early, using a setup that is not necessary and only slows down the story.

Also, there will be scenes that end too late, dragging on with meaningless chat after the point of the scene has been made.

Look at the dialogue. Most six-line speeches can be trimmed to two or three lines without losing anything. Look for idle chat — nothing slows down a story narrative more than chatter. Look for expository dialogue (talk that is primarily informational) and find visual ways to present the same information.

Sometimes a beginner will improve the economy so much that the pagination of a script slips below minimum standards (about 90 pages today). If this happens to you, then you need to find ways to beef up your story and make it more complex, requiring new scenes to bring the pagination up.

This is a conceptual change, not an exercise in padding! If you don’t add story elements, you will be padding, which is the opposite of your rewriting charge to make the script tighter.

I tell my students that “the chainsaw is your friend.” Therefore, use it! This becomes a mantra in my screenwriting classes.

Make sure to read our related article for a deeper look into streamlining your draft:

Minimalist Screenplay Tips for Maximum Punch

Crank It Up

Look for ways to crank up your story, making everything matter more.

For example, a student of mine wrote a scene in which a husband moves out after believing (wrongly, it turns out) that his wife is having an affair. The wife, who is the protagonist, has been flirting with her old high school boyfriend, who has appeared out of nowhere. The story is about how the wife comes to appreciate, after a marital crisis, how good her marriage really is.

On rewrite, the student “cranked up” the scene above by having the husband take the children with him when he left. Suddenly the stakes are much higher! This is one way to crank up a scene to make it matter more.

Take your time during the rewriting process. Now is the time to let things spin around in your head; there’s no hurry. If you strengthen the focus on the protagonist, make the script tighter and more efficient, and raise the stakes in the story, you’ll be on your way toward a much improved second draft.

<<<BACK TO

‘LEARN SCREENWRITING‘

Make Cinema Your Language

Cinema is a language we all understand, but not everyone ‘speaks’ it–directors do.

This interactive, self-guided textbook is a director’s toolbox, made for Apple Books.

Embrace a solid foundation with a future-proof, classic combo of theory, technique, history, and critical thinking.

Gain practical, adaptable creative skills and insight that transcend technological changes, be it a camera, mobile device, or AI.